How the Other Half Builds: Small-Scale Development in Tertiary Markets

Release Date: December 2021

Institutional commercial real estate investors and large development firms usually focus on the largest commercial real estate markets, though many are also active in mid-sized markets. Often referred to as “primary” and “secondary” markets, these roughly correspond to the 50 largest metropolitan areas in the U.S. By comparison, smaller “tertiary” markets attract less institutional investment and subsequently less attention from researchers, analysts and trade publications. New office and industrial buildings that serve these markets also tend to be smaller on average than those in larger markets, since local demand supports fewer multistory office buildings and large distribution centers. However, while they may not be at the center of the action, tertiary markets are home to about half the U.S. population and represent a significant share of the commercial real estate market.

Real estate development and ownership in smaller markets differs from development and ownership in larger markets in ways that tend to deter large regional or national developers and favor local developers. This research brief draws from a survey of NAIOP members and interviews with developers in tertiary markets such as Western Michigan and Southwest Missouri to examine these differences and their implications for developers and investors. The survey revealed that the broader community of developers and building owners prefer large projects in primary markets over small building development in tertiary markets for a variety of reasons. Conversely, developers who are active in tertiary markets identified several advantages to smaller-scale development in these markets. These divergent perspectives reflect differences between the two groups in their business strategy, scope of operations and familiarity with smaller markets. Large development firms may have good reasons to avoid smaller markets, but that does not mean they do not present opportunities for local developers and investors. To the contrary, local developers frequently cite the absence of larger competitors as one of the advantages of doing business in smaller markets.

Key Findings

|

Results from the Survey

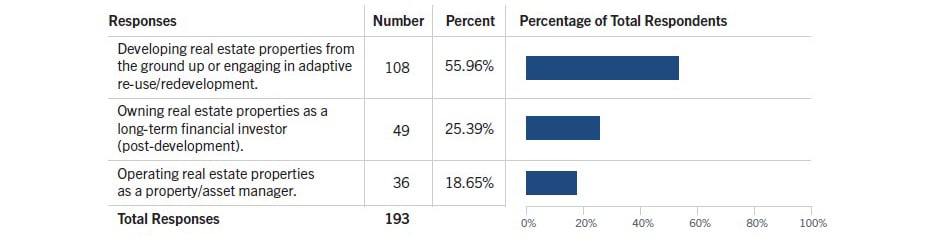

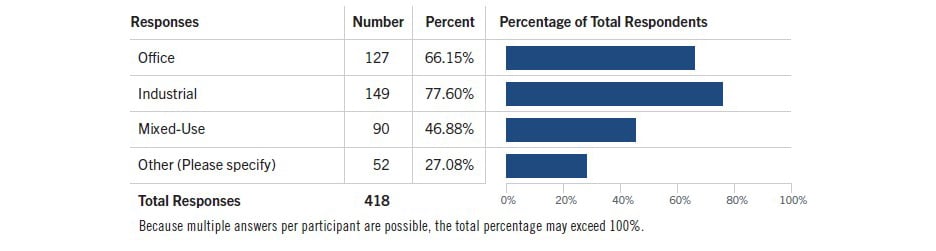

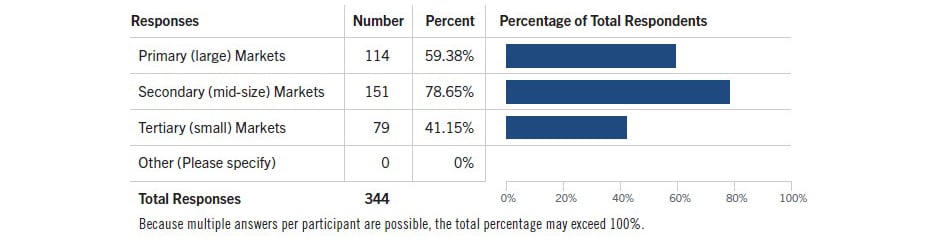

In August 2021, the NAIOP Research Foundation surveyed NAIOP members in the U.S. and Canada on their perceptions of how developing and owning small buildings in tertiary markets compares to developing and owning large buildings in primary markets. A total of 193 respondents who develop, invest in or operate real estate completed the survey. Notably, only 41.2% of respondents reported having experience in tertiary markets. Consequently, the results of the survey predominantly reflect the perspective of commercial real estate professionals who have limited experience in tertiary markets. They are nonetheless a useful measurement of how the commercial real estate industry as a whole perceives smaller buildings in smaller markets.

A few results reflect a relatively straightforward description of conditions in tertiary markets. Respondents on average indicated that rental and other income per square foot, as well as operating expenses per square foot, tend to be lower in these markets than in primary markets, while first-year cap rates tend to be higher. These conditions are to be expected in less dense areas that have lower land costs, average incomes and costs of living, as well as lower volumes of commercial real estate market activity.

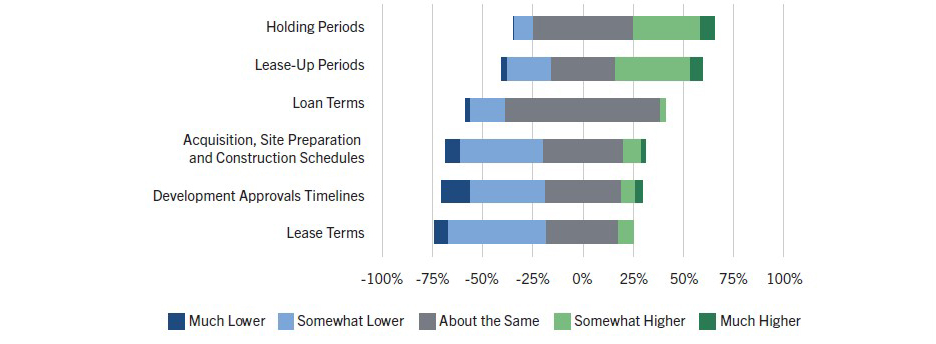

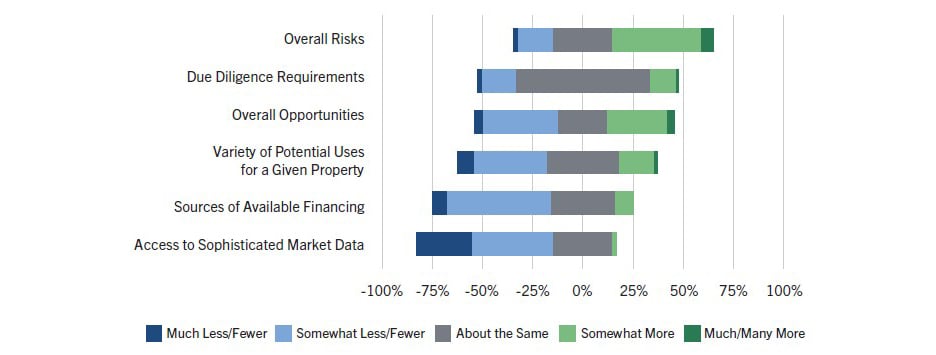

However, on balance, the results of the survey suggested less favorable risk/reward characteristics for smaller buildings in tertiary markets than larger buildings in primary markets. Respondents indicated that small building projects in tertiary markets present more overall risks and slightly fewer opportunities, have access to fewer sources of available financing and sophisticated market data, attract tenants with lower credit quality, experience slightly higher collection losses, take longer to lease up, have shorter lease terms, require longer holding periods and experience slightly lower net operating income growth. However, they also indicated that vacancy rates for small buildings in tertiary markets are about the same as they are for large buildings in primary markets, and most maintained that interest rates and loan terms were also about the same. Respondents did note some significant advantages to developing smaller buildings in tertiary markets: shorter development approvals timelines and acquisition, site preparation and construction schedules. A complete breakdown of the survey results is available at the end of the report. Selected quotes from survey respondents appear throughout this brief.

While survey and interview respondents broadly agree about several aspects of developing and owning small buildings in tertiary markets, interviews with developers who focus primarily on tertiary markets reveal a much different perspective on the relative advantages and disadvantages that these markets present.

A Note About Market DefinitionsThis research brief refers to smaller commercial real estate markets as “tertiary markets,” a commonly accepted classification that nonetheless is not clearly defined or uniformly applied by market participants. As discussed in the 2020 NAIOP Research Foundation Report “A New Look at Market Tier and Ranking Systems,” these systems regularly classify markets using different criteria, and many focus on the markets that fall into the top two tiers (primary/secondary, tier 1/tier 2, 24-hour/18-hour), with less attention paid to the characteristics of tertiary markets. In this brief, the term is only used to describe a market’s relative size and does not refer to other characteristics that are often considered by market-tier classification systems. A frequently cited rule of thumb for identifying tertiary markets is that they have fewer than 2 million people.1 This population threshold generally refers to metropolitan areas that are commonly grouped together as real estate markets, rather than individual cities, as only the four largest cities in the U.S. have more than 2 million residents. However, several markets that reside in census-defined metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) with fewer than 2 million people are commonly categorized as secondary markets, including Nashville, New Orleans and Salt Lake City. This discrepancy sometimes leads observers to identify additional criteria that differentiate secondary from tertiary markets, such as whether a market is home to a major sports team. In practice, commercial real estate professionals usually categorize several markets that are in MSAs with between 1 million and 2 million people and most of those in MSAs with fewer than 1 million people as tertiary. And most would also agree that commercial real estate development in markets like Akron, Ohio; Portland, Maine; Pensacola, Florida; or Visalia, California, differs in important respects from development in markets like New York, Los Angeles, Chicago or Dallas. Although tertiary markets usually attract limited attention from analysts, they represent a sizeable portion of commercial real estate in the U.S. Just over half of the U.S. population (51.3%) resides in MSAs that are home to fewer than 2 million people or in areas that are not included in an MSA.2 As with larger markets, there is substantial variation in the size, trajectory and characteristics of different tertiary markets. The health of an area’s economy, whether its population is growing or shrinking, and its dominant industries all affect demand for office, industrial, multifamily and retail real estate. Consequently, some markets are better for new development than others. Despite this variation, tertiary commercial real estate markets tend to share some common characteristics that differentiate them from larger markets. |

Investment and Development in Tertiary Markets

“In small markets, you have to be a generalist.”

– Survey Respondent

“Another advantage is less competition.”

– Survey Respondent

Survey and interview respondents agree that commercial real estate development in smaller markets is predominantly conducted by local developers and investors. Developers usually work in privately held firms—owned by sole practitioners, partnerships, families or employees—and attract investment from local private equity sources such as family firms or affluent individuals. General contractors may also act as developers for owner-operators who commission their own buildings. Most financing comes from community and regional banks.

Large multistate developers and institutional investors have historically played a small and infrequent role in development within these markets, though there are notable exceptions. For example, the expansion of Amazon’s distribution network has brought large distribution centers, and Amazon’s preferred development teams, to several smaller markets.

Open-ended comments from the survey and observations from interview respondents also suggest that since smaller markets produce a smaller volume of commercial projects, developers often choose to be generalists. Michael Garrett, president and CEO of Pinnacle Construction Group in Grand Rapids, Michigan, observed that to be the case in Western Michigan and with his own firm. Pinnacle is both a general contractor and a developer of industrial, medical, multifamily, office and retail real estate. According to Garrett, it is common for local general contractors with an established reputation to gradually take on development projects on the side.

Some regional developers who specialize in niche product types are also active in smaller markets. One example is Agracel, Inc., which specializes in building manufacturing facilities in small towns and which has developed properties in 21 states, according to Agracel’s president and CEO, Dean Bingham. However, survey and interview respondents suggest that the large developers that are active in major metropolitan areas are infrequent players in smaller markets. Respondents who are active in smaller markets cite the lack of competition from larger firms as one advantage to working in those markets. However, there are also several reasons why larger developers tend to avoid smaller projects in smaller markets.

Smaller Projects Favored by Long-Term Investors

Commercial real estate projects in smaller markets reflect the needs of occupiers in those markets and are generally smaller in both the size of the investment and the physical space a building occupies than similar projects in larger metropolitan areas. For example, interview respondents described the typical industrial buildings they worked on and that were common in their markets as ranging in size from 50,000 to 130,000 square feet, with typical deals ranging in size from $3 million to $10 million. Warehouses and distribution centers at this size are usually large enough to serve the needs of the local market. According to Bingham, 100,000-square-foot buildings are also usually optimal for manufacturing facilities that serve regional and national markets.

“Developing smaller buildings is fraught with obstacles that don’t pencil out on a cost-per-square-foot basis. Pre-development is just about the same as for a larger building. Contractors are not as competitive, and general-condition construction costs are much higher per square foot. This is not a knock against tertiary markets; rather, it is a knock against the economics of constructing small buildings. In my experience, the risk/reward relationship for small buildings is prohibitive.”

– Survey Respondent

“There are a lot of benefits to smaller buildings in smaller markets. One concern is often the exit [risk], but many pay for themselves over the initial primary lease period, which limits overall risk.”

– Survey Respondent

Development firms that focus on achieving economies of scale with larger projects may not find these smaller projects worth pursuing. Merchant developers that earn most of their returns on acquisition, development and disposition also tend to avoid smaller markets because they are generally less liquid than larger markets, with fewer buyers looking for commercial buildings at any given time. Exit risk—the risk that a buyer may not be available when it is time to sell—can be a significant concern for a developer with financing or investor commitments that require completing and selling a building in a narrow timeframe. Less liquidity is one reason that properties in smaller markets trade at higher cap rates than similar properties in larger markets. Higher exit risk and higher yields in smaller markets lead developers in these markets to favor longer holding periods, with a large share of the profit from a typical project coming from owning and operating the building.

Like the large developers they often partner with, institutional investors have tended to avoid smaller markets because they do not usually offer deals that compare in size to those in larger markets. Rick Tollakson, president and CEO of Hubbell Realty Company in West Des Moines, Iowa, observed that institutional investors generally prefer to invest in larger projects since it is easier for them to evaluate and monitor a small number of large projects than a large number of small projects. Every new deal comes with transaction costs, and as with construction costs, investors can realize economies of scale by focusing on larger transactions.

This dynamic may be changing for industrial markets, however, as cap rate compression in the largest markets appears to be leading some larger investors to look further afield for higher yields. Bingham observed that industrial REITs have become increasingly active in the smaller cities and towns where Agracel is active. Given the currently weak market for office development, he has also noticed more investors that traditionally focused on office properties looking at industrial opportunities in smaller markets.

Agracel developed this 105,000 square-foot build-to-suit manufacturing facility for Horton in Westminster, South Carolina. Photo courtesy of Agracel, Inc.

An Informational and Reputational Advantage for Local Developers

Limited market research for smaller markets is another factor that tends to favor local developers over regional or national developers. Commercial real estate services firms generally publish only limited information about tertiary markets. Since smaller markets produce a smaller volume of commercial real estate transactions, it can be harder to estimate an appropriate valuation for existing real estate or what a future building could sell for. Limited data on local economies can also make it difficult for outsiders to evaluate whether a building will lease up quickly or remain vacant for a prolonged period. Experienced local developers have an informational advantage over outside developers: they are familiar with their local markets, can more easily identify suitable tenants for their properties, and can more easily estimate acquisition and development costs. In Agracel’s case, the firm’s experience with development in many smaller markets has provided it a similar advantage over other developers with a large geographic scope, allowing it to more easily assess the risks and opportunities associated with a project in a smaller market.

“Localized anecdotal demand in small markets frequently overstates the true depth of demand, resulting in long initial lease-ups and protracted vacancies on turnover.”

– Survey Respondent

Developers who are active in tertiary markets report relying on recent experience and strong relationships with occupiers to gauge demand for new development. Garrett indicated that a large share of Pinnacle’s project volume is the result of demand from existing partners. For example, his firm is currently building restaurants and golf clubs for a hospitality group and has been working on a steady stream of projects for multifamily operators. About half of the firm’s projects are preleased, and purely speculative buildings are usually leased within a year from project start. Tom Rankin, owner of Rankin Development in Springfield, Missouri, which specializes in industrial development, pursues a roughly even balance of speculative and build-to-suit projects. He is familiar with what occupiers in his market want but limits risk by only pursuing a single speculative project at a time. He observed that his colleagues in larger markets are often more comfortable developing multiple speculative projects at a time since they can be more confident that their markets will quickly absorb the space. Bingham shared that Agracel limits risk by focusing on projects for which it has already identified a tenant or buyer.

Tenants and Owner-Occupiers

“The smallest-footprint offices have been leasing surprisingly well. Also, there is a lot of demand for these small buildings in the owner-user market.”

– Survey Respondent

Interview respondents indicated that most commercial real estate in tertiary markets is occupied by local and regional tenants and owner-operators, though national and international tenants who are interested in serving local markets can make up a sizeable portion of the tenant base in many smaller markets. National firms that have historic ties to a region may also have a significant office presence in smaller markets. By contrast, major logistics firms are less likely to locate large distribution facilities in smaller markets that are far from larger metropolitan areas.

The small businesses that occupy a substantial share of commercial real estate in smaller markets often have different needs and expectations than national tenants or larger regional firms. Rankin observed that small businesses usually need more guidance throughout the development process. They know what they want from a building but look to the developer to translate their needs to the design and construction team. He also shared that they are often more focused on project costs than national tenants, who tend to be more concerned with how quickly a project can be completed.

Amazon has opened several large facilities in tertiary markets across the U.S. The 1.3 million square-foot Amazon fulfillment center pictured here is adjacent to four 130,000 square-foot industrial buildings that Rankin Development built in Republic, Missouri. A different tenant occupies each of Rankin’s four buildings. Photo courtesy of Rankin Development.

When it comes to leases, Garrett noted that small business owners are usually more accepting of developer-friendly lease terms, but these terms also reflect the additional risk that his firm takes on these tenants, some of whom have not previously leased commercial space. He added that Pinnacle offers these tenants more flexibility than they could expect from a larger landlord, and that leases for small businesses are simpler than those the firm executes with larger tenants. Rankin observed that small businesses often have different expectations for lease length and may seek shorter terms than he is willing to offer, though they usually settle for a lease that is at least five years in length.

As in any market, tenants in smaller markets occupy spaces that reflect their size and scope of operations. Within the industrial market, Rankin observed that small business owners might start by owning their own small warehouse before expanding into a larger leased space. Whether building for a local small business or a national firm, he usually builds new industrial buildings with 32-foot clear heights, taller than most industrial buildings in the area. This helps ensure the buildings will meet future tenants’ needs when it is time to re-lease them.

Garrett has found that local tenants tend to prefer to customize their own buildings, while speculative flex industrial multitenant buildings are attractive to regional, national and international tenants who seek cost-effective access to cities and towns in Western Michigan. For these out-of-state tenants, the office component in a flex building is often just as important as the distribution space, with some dedicating most of the space within these buildings to office space. Although national tenants often seek 36-foot clear heights for warehouse and distribution facilities, 24-foot clear buildings remain the norm in his market, since they provide low-cost space that meets the needs of the local market. Developers in his market have also found it profitable to convert old steel plants and furniture factories into warehouse and distribution facilities.

Bingham observed that manufacturers are often drawn to rural areas and small towns that are located within a reasonable distance from raw materials, a major customer or a major logistics hub. Land and labor costs are lower in these areas but still meet a manufacturer’s locational needs. While it can be more difficult to re-lease or sell a custom-designed manufacturing facility than a similarly sized distribution facility, manufacturers typically lease a building for many years to recoup their capital investment. For a typical $5 million building, a manufacturer might invest $15 million in equipment that itself could require another $1 million to install.

As with larger markets, interview respondents in tertiary markets report strong industrial development activity, with fewer retail or office deals. They also have observed that in recent years, national tenants have constituted a growing share of the occupiers for industrial real estate in their markets, reflecting growth in e-commerce distribution across the U.S. For example, Rankin has seen larger tenants gradually drawn to the area around Springfield, Missouri, as that consumer market has grown, with a recent acceleration of leasing to shorten delivery timelines. Garrett notes that while industrial activity is robust relative to previous years, his market does not experience the same degree of variation in market activity that is common in larger markets, which tend to experience larger booms and busts. While not all smaller markets may be as stable as Western Michigan or Southwest Missouri, the historical tendency for larger investors and developers to avoid tertiary markets may limit volatility from rapid changes in deal volume.

Development Timelines and Costs

Unsurprisingly, one thing that both survey and interview respondents agree on is that development timelines for small buildings in tertiary markets are usually shorter than they are for large buildings in larger markets. Interview respondents indicated that smaller markets are usually more welcoming of development and are much quicker to complete development approvals. According to Bingham, plan reviews can be completed and permits issued within a month for many projects in smaller cities and towns.

“Just because the market is tertiary, do not assume that the overall development cost will be lower.

The land cost will certainly be less, but construction costs [tend] to be higher due to lack of competitive subcontractors.”

– Survey Respondent

Land costs in smaller markets are generally lower than in larger markets, but some survey respondents shared that in their experience, construction costs in tertiary markets or for smaller buildings were higher than for larger buildings in larger markets due to lower levels of competition among contractors or because smaller buildings lacked economies of scale. By contrast, Garrett and Rankin maintained that construction markets in their areas are cost competitive. However, nonlocal developers may not have established relationships with local contractors that would allow them to identify the best candidates for a project, or to obtain the best rates. Rankin shared that he regularly uses the same general contractor, architect and civil engineer, allowing his firm to quickly put together specifications for a new building, price it and build it. Garrett observed that when larger developers have attempted to enter the Western Michigan market in the past, they have struggled to compete with local developers because they did not have established relationships with local construction firms.

Rankin observed that although construction markets are competitive, his firm does face less competition from other developers than he would expect to see in larger markets. While this presents clear advantages, it also means there are fewer local opportunities for networking and knowledge sharing. Organizations like NAIOP present an opportunity for developers in smaller markets to develop larger networks and learn from what developers are doing in other markets, and Rankin credits his membership in NAIOP and its National Forums program as an important contributor to his success.

Although development timelines are generally shorter in tertiary markets, local developers noted that this advantage has been temporarily blunted by the pandemic. Key building material and component deliveries have been delayed by several months due to supply chain disruptions. Although developers in larger markets face the same constraints, the relative effect on their timelines is less pronounced, since they already need to wait several months for development approvals to be finalized and can order construction materials that are in short supply during this window. Bingham also expects that lower mask usage in many smaller markets is leading to more frequent worker quarantines than in markets where workers more closely follow COVID-19 safety protocols.

Conclusion

Unlike larger markets—which generally boast diverse economies that support a range of different occupiers and commercial projects—local economic and business conditions, dominant industries and locational advantages vary substantially between different tertiary markets. Since little market research is available for smaller markets, developers must take additional time and effort to evaluate individual markets to find suitable locations and develop realistic projections of acquisition costs, construction costs and future cash flows. Developers who focus on tertiary markets—most often, local developers—develop a familiarity with these markets that allows them to evaluate potential projects more easily. These developers also establish relationships with design and construction teams that facilitate project completion and reputations that attract business from local and regional occupiers.

Tertiary markets are not a good fit for every developer. Many will instead prefer larger markets where they can complete larger buildings and sell them shortly after they are fully leased. However, smaller markets also present notable advantages: quicker project timelines, higher yields and less competition from other developers. They require a different strategy than those usually followed by developers in larger markets but offer advantages for developers willing to take the time to familiarize themselves with local market dynamics and make long-term investments in growing communities.

Interview Participants

Dean Bingham, president and CEO, Agracel, Inc.

Michael Garrett, president and CEO, Pinnacle Construction Group

Tom Rankin, CCIM, owner, Rankin Development

Survey Data

1. On average across all commercial property types, small buildings (e.g., office buildings smaller than 10,000 square feet or industrial buildings smaller than 100,000 square feet) in tertiary markets have ______ vs. large buildings in primary markets.

2. On average across all commercial property types, small buildings in tertiary markets have ______ vs. large buildings in primary markets.

3. On average across all commercial property types, small buildings in tertiary markets face/present ______ vs. large buildings in primary markets.

Respondent Profile

Which of the following best describes your involvement with real estate properties?

In what building type(s) have you been involved with development, ownership, or operations? (Select all that apply.)

Where have those buildings been located? (Select all that apply.)

About NAIOP

NAIOP, the Commercial Real Estate Development Association, is the leading organization for developers, owners and related professionals in office, industrial, retail and mixed-use real estate. NAIOP comprises some 20,000 members in North America. NAIOP advances responsible commercial real estate development and advocates for effective public policy. For more information, visit naiop.org.

The NAIOP Research Foundation was established in 2000 as a 501(c)(3) organization to support the work of individuals and organizations engaged in real estate development, investment and operations. The Foundation’s core purpose is to provide information about how real properties, especially office, industrial and mixed-use properties, impact and benefit communities throughout North America. The initial funding for the Research Foundation was underwritten by NAIOP and its Founding Governors with an endowment established to support future research. For more information, visit naiop.org/researchfoundation.

About the Author

Shawn Moura, Ph.D., is director of research at NAIOP. To submit questions or comments about this research brief, contact moura@naiop.org.

Media Inquiries

Please contact Kathryn Hamilton, vice president for marketing and communications, at hamilton@naiop.org.

Disclaimer

This project is intended to provide information and insights to industry practitioners and does not constitute advice or recommendations. NAIOP disclaims any liability for actions taken as a result of this project and its findings. © 2021 NAIOP Research Foundation

Endnotes

1 Drew Dolan, “Understanding Secondary, Tertiary Markets and the Value of Their Real Estate Investment Offerings,” Forbes, August 29, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesrealestatecouncil/2018/08/29/understanding-secondary-tertiary-markets-and-the-value-of-their-real-estate-investment-offerings/?sh=59566187753d.

2 United States Census Bureau, “Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Area Tables,” https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/metro-micro/data/tables.html.