What’s Working and What’s Not Working in CRE

An economist’s take on how we got here and what to watch in 2024.

A plethora of media coverage regarding “what’s not working” in commercial real estate has taken place since the beginning of 2023, but most of that coverage has been targeted at the outer layers of a deeper and more systemic set of challenges confronting the industry. To better understand what’s not working, the use of a visual image is helpful. In this case, imagine peeling back the layers of an onion to see what lies beneath (and what could potentially make CRE investors and lenders cry in 2024).

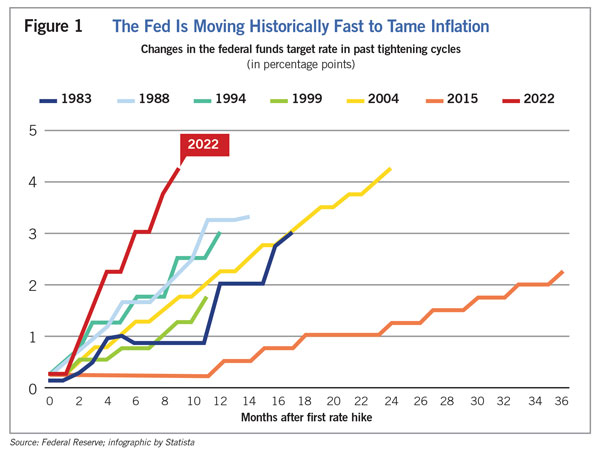

The obvious problematic outer layers are the Federal Reserve, interest rates and declining CRE values at a time when approximately $1.5 trillion of CRE faces refinancing by early 2025. The Federal Reserve embarked on a historically fast and steep rate-hiking cycle beginning in March 2022 after stating that COVID-induced inflation was transitory (followed by an eventual admission that it was not transitory). Interest rate hikes commenced modestly with 25 basis points (bps) in March 2022, followed by 50 bps in May, and then four successive 75-bp hikes. There was no pause until September 2023, following 11 consecutive hikes. Figure 1 illustrates the rate-hiking cycle within a historical context. The red line shows the current 2022-2023 rate-hiking cycle (as of mid-2023). The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), led by Jerome Powell, has done what has never been done before (not even by former Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker in the late 1970s and early 1980s), increasing interest rates 11 times within 18 months with no pause for assessment.

Then came the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in March 2023. It became apparent that the aggressive rate hikes had created an imbalance between bank assets (loans and fixed-rate instruments like Treasury bonds and real estate loans) and liabilities (deposits) that would ripple through the debt-dependent CRE industry.

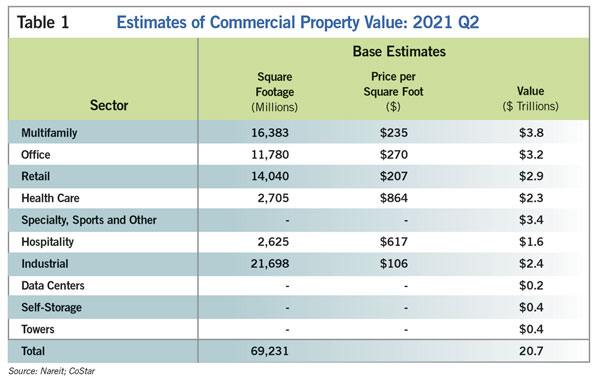

Exacerbating the financing problem is that the Federal Reserve has broken the decades-old net–interest margin (NIM) model that sustained banks through every crisis going back to the 1970s. As part of the NIM model, banks have traditionally paid depositors a nominal amount of 1% to 3% for deposits and then lent those funds (liabilities) out at a positive spread of 300 bps to 400 bps, fueling lending growth in areas such as construction loans. Currently, banks have to pay more for deposits (5% to 7%) than their existing loans pay (less than 5%). As a result, many banks (especially CRE-concentrated banks) have a negative NIM that is inhibiting all aspects of CRE lending, from construction loans to permanent commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) and GSE (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) multifamily loan originations. Essentially, banks are now facing CRE lending headwinds that go well beyond CRE concentration (100% and 300% of capital limits). It is an extremely strong headwind for CRE because banks lack the profitability and margin to lend into a nearly $21 trillion CRE market (see Table 1).

This “no capital for nobody” layer of the onion has been peeled back by three events. The first was the April 2023 assessment of the SVB bank failure by the Federal Reserve in which it concluded, in part, that it “did not fully appreciate the extent of the vulnerabilities as Silicon Valley Bank grew in size and complexity.” In other words, bank supervision had once again failed. Despite this forensic report and supervisory failings, the Federal Reserve went ahead with the second event: its annual stress test of the 23 largest U.S. banks. The Fed concluded on June 28 that all banks had passed, were healthy and were well-capitalized. The ratings agencies, however, were skeptical of this claim and subsequently embarked on the third event: downgrading the same banks and banking system the Federal Reserve has been selling as healthy.

These three events have resulted in the most significant “what’s not working” layer for CRE — capital lockup. Regardless of the property type, borrower credit or metropolitan statistical area (MSA), banks are contracting debt capital, and the permanent CMBS loan market has contracted by 80% year over year and is heading toward the same legacy fate it incurred in 2009. CRE requires both “water spigots” (construction lending by banks and a permanent CMBS market for banks to offload stabilized construction loans to replenish capital for new lending activity) to be open and flowing debt capital for the industry to be “working.”

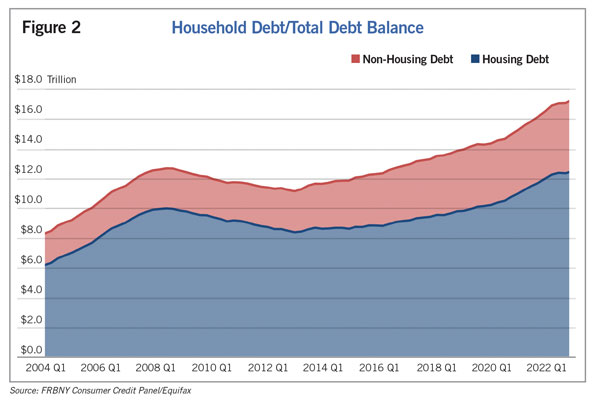

Another layer to address is household debt (see Figure 2), which is affecting real estate sectors from housing to retail. According to the New York Federal Reserve Bank’s Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit, household debt continues to climb and reach new levels. In the third quarter of 2023, total household debt rose to $17.29 trillion (a record), while credit card balances grew to $1.08 trillion. Households are being challenged by inflation, but more so by the higher interest rates on that increasing debt, which will affect consumer spending (retail and industrial sectors) and the amount available for housing costs (multifamily sector).

What’s Working in CRE

So, if a capital lockup is at the core of what’s not working, what is working in our CRE industry? First, it is important to recognize that the economic and CRE down cycles were not caused by commercial real estate developers, lenders or investors. After the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-2011, the CRE industry has been quite disciplined. It did not overbuild. It did not overleverage. And it did not engage in exotic finance schemes like subprime mortgages. This point is fundamental to realizing that if capital can get flowing again at reasonable interest rates (the Fed’s overnight bank lending rate would need to go below the current 5.3% to a level in the range of 4%), a lot will get working again in the CRE industry.

CRE professionals are advised to anticipate the following moving forward:

- More CRE value contraction as maturing CRE debt gets repriced with interest rates in the 7% to 8% range and cap rates 200 bps to 400 bps higher than when those loans were originated.

- More equity in transactions to offset the debt contraction.

- Development of new capital relationships such as credit unions (yes, they are CRE lenders and can syndicate larger loans among themselves), family and friends funds, private equity not focused on the vulture feeding frenzy for distressed office buildings, and even sale-leaseback structures to retire debt and salvage the operations of assets (resort and luxury hotels executed on this strategy during the early days of COVID when banks panicked).

- Less new supply as construction lending in banks grinds to a standstill.

Recognizing all of the aforementioned, which sectors and locations are examplesof “what is working”?

Connectivity to Gulf ports such as Mobile, Alabama, is a selling point for many tenants of industrial real estate. Art Wager via iStock/Getty Images Plus

Industrial

Industrial real estate is top of the list, but even this property type is undergoing change. Tenants are conveying to developers that they want to pause on “biggie-size-it” development and instead are opting for 100,000- to 300,000-square-foot warehouses to hedge their long-term risks. However, the tenants/occupiers want this new “small-size-it” warehousing to be: flexible, located in industrial parks that have additional land for expansion and located in proximity to ports and key logistics infrastructure (especially along rail) near emerging inland ports (the newest being in Montgomery, Alabama, and the most overlooked being in Little Rock, Arkansas), and with connectivity to the Gulf and Southeast ports in Georgia (Savannah), South Carolina (Charleston), Florida (Port Everglades), Alabama (Mobile), Louisiana and Texas (Port Freeport). The ports of Mobile and Port Freeport (south of Houston) are two of the most notable ports to watch.

Another area that’s working in industrial space is cold storage. The average age of a cold storage warehouse is 37 years, and most of these assets are functionally obsolete. New cold storage development represents less than 2% percent of all new industrial development, so there is little risk of overbuilding. However, it is not for the “faint of capital” because the costs are high and tenant requirements vary substantially.

Multifamily

In the multifamily sector, all but three of the top 15 MSAs in year-over-year rent growth are in the Midwest, according to RealPage’s first-half 2023 data. The fuel in this engine is migration toward affordability and MSAs with skilled workforces, from Wichita, Kansas, to Columbus, Ohio.

Affordability and skilled workforces have raised the appeal of Midwestern locales such as Wichita, Kansas, in the multifamily sector. Sean Pavone via iStock/Getty Images Plus

The PODS Moving Trends report is a relatively new source of data to track current workforce and population migrations. According to the August 2023 report, the Myrtle Beach, South Carolina/Wilmington, North Carolina, area was the No. 1 place people moved to in 2022. Sarasota, Florida; Orlando, Florida; Ocala, Florida; and Houston rounded out the top-five destinations for PODS containers in 2022. The report also noted that 2022 was “the second year in a row that southern states have seen a larger influx of residents compared to any other region, with more than 80% of the destinations on the list being in the south.”

Conclusion

Many other areas are still working in the CRE industry, but there is limited space here to highlight them all. New homebuilders are working and able to sell new homes with interest rate buy-down programs that existing homeowners don’t have access to. Manufactured housing is working but faces NIMBY headwinds in every state. Amenitized, well-located suburban office buildings are far outperforming urban and central business district buildings in large MSAs because they are close to where the workforce lives and wants to work. The Midwest and South are the two regions performing best from a geographical perspective because they offer affordable lifestyles, educated workforces from nearby universities, and CRE inventory at affordable prices.

Christopher Robb, a stock analyst at Seeking Alpha, recently captured the essence of forecasting this economy and distinguishing what’s working from what’s not working: “Accepting that many correlations that have traditionally provided insight may no longer be functional is essential to navigating today’s markets.”

In other words, the data and metrics we have relied on in prior down cycles and CRE recessions (such as unemployment and vacancies) may no longer be insightful and valid. Look to household debt and fresh industry data from the likes of PODS and the National Center for the Middle Market, entities such as Visual Capitalist and Statista, and industry organizations like NAIOP for the windshield view.

K.C. Conway, MAI, CCIM, CRE, is a commercial real estate economist and futurist based in Atlanta.

RELATED ARTICLES YOU MAY LIKE

From the Editor: As the Economy Improves, What’s Next for CRE?

As of this summer, it appears that the Fed may have engineered a soft landing for the U.S. economy.

Read More

Worth Repeating

Sounds bites from NAIOP’s I.CON East, held June 7-8 in Jersey City, New Jersey.

Read More

CEO on Leadership: Andrew VanHorn

The new president and chief development officer for Dweck Properties in Washington, D.C., talks about leadership, culture and growing a new commercial real estate company focused on multifamily.

Read More