Preparing a Large Property Portfolio for the Future

Cambridge, Massachusetts, has launched an ambitious program to update its historic public buildings.

For municipalities across the U.S., the maintenance of public buildings has always been a necessary — and underfunded — task. But today, with the impacts of energy costs, unpredictable weather and other factors, maintaining the status quo is no longer enough. America’s aging building stock should be updated thoughtfully and proactively to meet both current and future challenges.

It’s not easy. Municipal facilities run the gamut from administrative office buildings to police and fire stations, public gathering spaces to youth and senior centers, city halls to libraries, and more. Each of these buildings has unique needs; some may date back centuries, while others are just decades old but require ongoing maintenance and have equipment that is nearing the end of its useful life. In many cases, costs can quickly exceed budgets, and coordinating the maintenance of buildings at various stages of disrepair becomes overwhelming.

The city management of Cambridge, Massachusetts, knows this well. Cambridge, first settled in 1631, is one of America’s oldest cities. And while its municipal building stock may not date back to the 17th century, over half of its municipal portfolio (excluding schools) is historically significant and has considerable deferred-maintenance needs. The regular work required to maintain the structures is time-consuming and expensive, and the costs of heating and cooling them are increasing.

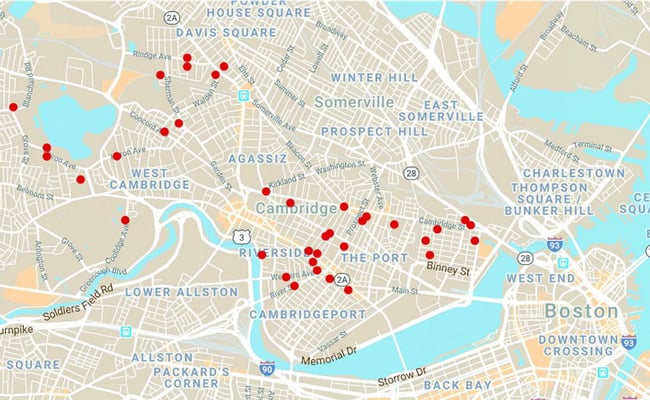

Buildings included in the Cambridge Municipal Facilities Improvement Plan were located throughout the city. Image courtesy of ICON Architecture

In 2013, the city established a task force to figure out how Cambridge could become a “Net Zero community,” with sharply reduced energy needs met primarily via renewable sources. Composed of residents, business and property owners, developers and representatives from local universities, the task force ultimately drafted a Net Zero Action Plan, which was approved and adopted by the Cambridge City Council in 2015. The city was now officially committed to improving energy efficiency in its public buildings and supporting the development of renewable energy sources.

The city established funding and sent out a RFQ seeking to develop a Municipal Facilities Improvement Plan (MFIP). The partnership of Arup, the New Buildings Institute and Boston-based ICON Architecture had the winning bid. Rebecca Hatchadorian, LEED AP, BD&C, WELL AP, who oversees sustainability efforts at Arup Boston, and Ned Collier, AIA LEED AP, principal of the Education Studio at ICON, began the effort of developing and implementing the MFIP. In 2016, Julie Lynch, AIA, became the Municipal Facilities Improvement Plan Project Manager for the City of Cambridge Department of Public Works (DPW).

Development magazine spoke with all three about the process of assessing the condition of Cambridge’s municipal buildings — from energy use to structural concerns, developing a plan to achieve immediate and more far-reaching goals, and issues and solutions encountered along the way.

The Work Begins

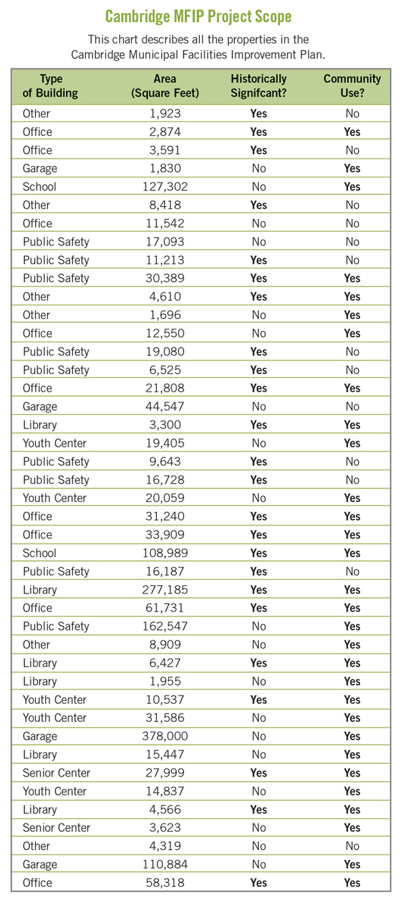

Forty-three buildings were included in the MFIP’s initial assessment package. These included seven firehouses and the city’s main fire headquarters, six libraries, five youth centers, two senior centers, a police/public safety building, a cemetery administration building and chapel, Cambridge City Hall and City Hall Annex, Department of Public Works buildings, several parking garages, a golf course clubhouse, a park comfort station and more. While the city’s school buildings were not officially part of the plan, two schools were included to help the team compare and provide information to Cambridge Schools leadership.

Before it was renovated, the reception desk at the Cambridge Traffic Department wasn’t easy for people with disabilities to use. After the renovation, the addition of vanity lighting on the inside of customer service windows helps those with visual impairments or who need to read lips see the faces of staff members more easily.Images courtesy of ICON Architecture

The assessment process kicked off with multidepartment work sessions facilitated by the San Francisco-based New Buildings Institute (NBI) and Arup.

“Holding a series of workshops with representation from every department in the city was an important step,” says Hatchadorian. “We had roughly 50 people discussing goals and priorities, and helping to determine whether we’d focus on just energy and carbon or set a larger list of priorities.”

Ultimately, recalls Collier, “a number of targeted issues raised in the workshops did result in a broader set of priorities.” These included life safety, comfort, accessibility and historic preservation. The team determined that these additional initiatives would be pursued as vigorously as the energy concerns.

The historic-preservation aspect was a crucial concern. Seven of the city’s buildings included in the MFIP were built in the late 1800s, and more than 90% were built prior to 2000. In all, 56% of the MFIP portfolio was identified as historically significant.

Another concern was resiliency.

“Resiliency — making buildings stronger and more robust — was certainly an emphasis,” says Hatchadorian. “We utilized the Vulnerability Assessment the city has already completed, looking at flood risk and heat, and pulled the results for individual buildings into our assessment. By putting all relevant information in one place, we could quickly and easily determine whether resilience should be prioritized for a particular building and project.”

Under Arup’s direction, ICON conducted site assessments in each building. They examined the condition of the building envelope, including the roof, windows and walls, and the indoor environmental quality.

The University of California at Berkley Center for the Built Environment’s Indoor Environmental Quality Survey was also used to assess the portfolio. It provided occupant feedback to complement the walk-throughs and energy analysis.

In conjunction with the city, they used a standardized seven-point assessment scale for each of the seven assessment categories, with rankings from -3 to +3, to allow for variation in scoring on given topics. The definition for each score was developed collaboratively between the team members.

Assessors provided scores in multiple categories, including energy use intensity (determined by dividing the sum of all energy used annually in the building by its total square footage), greenhouse gas emissions (including carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and ozone), indoor environmental quality in terms of lighting, acoustics, air quality, layout and more, as well as a careful review of exterior and interior architecture, and structural, mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems.

Sources for each building’s energy supply were also calculated, detailing, for example, the amount of energy provided through grid electricity vs. solar PV electricity.

Using software provided by the New Buildings Institute, the team got an in-depth read into issues facing each of the included buildings. For example, in the NBI’s report on the 33,909-square-foot City Hall Annex, cooling efficiency was rated “good,” while heating and ventilation efficiency received a “poor” rating.

“We looked at the thermal performance of the envelope, the air tightness and what’s called thermal bridging — where interior and exterior sections connect,” explains Collier. “These areas are notorious for allowing heat and cold to travel in and out.”

In its summary report, the NBI listed buildings it saw as strong candidates for “whole-building deep energy retrofits,” with others as prospects for “zero-net-energy retrofits.” Some were recommended for further investigation in the categories “high total energy use,” “high electric baseboard,” “shell & ventilation related efficiency” and “unusually high summer gas use.”

Each building received a list of action steps with estimated costs. Work was also done to determine regulatory codes and building compliance. Arup developed a standardized site assessment report for each building, including a preliminary list of immediate and long-term needs.

“To no one’s surprise, after the initial assessments, there were no scores that reached +3. The +3 was extremely aspirational,” Hatchadorian says. “For instance, on carbon, it was not just carbon neutral but carbon positive. For accessibility, it wasn’t simply compliance with MAAB/ADA standards, it was achieving Universal Design standards. Ultimately, we had a few buildings that reached +1. Those were the top ranking. On the other hand, the lowest rankings were -2’s.”

“Our consultant team didn’t know these buildings as well as the city did, so there were some surprises after we developed the scores and presented them to the city,” Hatchadorian adds. “There were some preconceived notions about the condition of certain buildings that led to some surprises in the results. For example, our assessments showed that some of their newest buildings weren’t among the best performing. One of the things that quickly became apparent was that the needs far outweighed the budget.”

Costs and Challenges

Now the team faced the challenging task of prioritizing — and paying for — improvements.

“We don’t have enough money and staff to do everything, so we chose our projects carefully,” says Lynch. “People expected scores to drive our plans, but there were other considerations, including how many people use the building. Some of these buildings have 100 employees, others have just one. Also, we’re renovating occupied buildings, which is adding another layer of costs. Another question we had to consider: Does the facility support community use, making it a higher priority?”

The project is expected to extend over multiple years. Funding via bonds and property taxes will be ongoing. For example, Cambridge’s budget for 2020 seeks $29 million for MFIP projects.

Site visits and building surveys highlighted another pressing issue: in many cases, substantial deferred-maintenance work was needed before deeper improvements could be considered.

“The firehouses, which are generally the oldest buildings, were in the worst condition,” says Lynch. “The first building I went to was a firehouse, and it was in such bad shape. I was shocked by the level of deferred maintenance.”

Because the initial budget hadn’t anticipated the breadth of needed improvements, the team began working closely with Lynch to manage costs and find funding.

It was here that the team recognized a core benefit to the multibuilding improvement approach while establishing material, equipment and detailing standards: the ability to consolidate projects and save money, time and materials in the short term, and to establish a more streamlined maintenance approach in the long run.

“What needs do we see in multiple buildings that we can put out as one bid? That sort of review allows us to do the bid process just once, saving time and effort,” says Hatchadorian. “We can also provide the city consistent products and materials and simplify construction by working with a singular contractor, saving money in construction as well. Also, replicable projects, meaning projects that maybe we don’t bid as one, but where we do work on one building and then do it again in other buildings. In these cases, we can be more efficient down the line, and when buildings receive the same mechanical systems, it gives the city a more streamlined way of maintaining them.”

Lynch agrees.

“In terms of standardization across the city, we worked with Arup, ICON, other designers and other city departments to develop standard specifications for HVAC control, lighting, audio visual, wayfinding and signage supporting Universal Design, glazing, keying, door hardware and plumbing fixtures,” she says. “For example, all HVAC equipment is tied into the existing Building Maintenance Systems (BMS) based on the HVAC controls standard, including two recent cooling tower replacements and an air source heat pump system. That makes it easier for our HVAC vendors and city technicians to ensure all of them are working as efficiently as possible.”

Hatchadorian recalls another project that streamlined maintenance through coordination and standardization: the purchase and installation of a standardized fire alarm notification system across multiple buildings, making servicing them much simpler.

The team identified more cost-saving solutions.

For example, the Massachusetts Green Communities Act, which was first passed in 2008, “put in place several mechanisms to encourage the implementation of energy efficiency and renewable energy projects, including streamlined procurement pathways for energy conservation measures and energy management services,” according to Boston’s Metropolitan Area Planning Council.

“It can simplify municipal procurement for energy efficiency projects by working with the local utility, in this case Eversource, which has competitively selected design/build firms,” says Lynch. “A municipality can contract for projects up to $100,000 with these firms. It’s a tool, and we’ve used it to contract on LED lights, heat pump projects and insulation.”

The team soon recognized that smaller, “one-off” projects weren’t always quick, and that an anticipated “small” project could rapidly lead to larger issues.

“We began taking a more holistic approach, trying to determine the big picture first,” says Hatchadorian.

Taking this wider overview of each project allows the team to schedule similar work at one time, and sometimes, to accomplish a variety of solutions at once.

Zooming In on Net Zero

Although deferred-maintenance projects occupied the team’s attention initially, energy concerns have been a core focus throughout the process.

“Keeping the city’s net-zero goals in mind, we’ve installed four solar PV projects,” says Hatchadorian. “We’re looking to supplement that work with grants from the state for energy storage feasibility studies.”

The city’s inefficient firehouses have also received attention, with insulation added in multiple facilities.

City Hall Annex and its unexpected energy issues has been another major focus.

“We’ve done a fair amount of work on City Hall Annex, which got LEED Gold certification back in the early 2000s,” says Collier. “However, we discovered that it’s never performed to those standards in terms of energy usage — it’s chronically fallen short. The building envelope underperforms, which overtaxes the mechanicals system.”

Solutions that the team has so far identified include repointing the annex’s brick exterior and replacing or reinstalling windows.

Human-Centered Design

But beyond anticipated energy, sustainability and resiliency solutions, ensuring that these facilities are well-designed and utilized has been another focus of the process.

“The city’s commitment to achieving Universal Design standards that go beyond the Massachusetts Architectural Access Board and the Americans with Disabilities Act requirements has impressed me,” says Collier.

He points to a relatively small improvement suggested by the team at Boston-based Institute for Human Centered Design: adding vanity lighting on the inside of customer service windows so that people with visual impairments or who need to read lips can see the faces of staff members more easily.

Considering the needs of 43 buildings at once has also allowed the city to better focus on the use of those spaces.

“The MFIP has really helped us determine whether we are using our existing buildings to the best of their ability,” says Lynch. “We discovered things like the top floor of the Inman Square Firehouse has been abandoned for decades. The building needs an elevator and new stairwell to allow us to take advantage of that space, so now we have one more thing to accomplish, but at least we’re aware of it.”

Other space issues were easier to resolve.

“One of my favorite projects was our renovation of the basement in the Coffin Building,” says Lynch. “We were able to relocate two social service groups, the Center for Families and Baby University, two highly utilized community services. These groups had been scattered across the city. When we turned that space over to them, they were so thrilled that we’d provide a centralized, well-designed space for them.”

Lessons Learned

The MFIP’s progress is being watched by other municipalities, as well as by commercial real estate owners and developers who might be seeking a template for their own building concerns.

“For public- and private-sector owners, the question is the same,” says Hatchadorian. “How do I make investments in the buildings I own and best use those funds to achieve multiple goals? This plan has demonstrated the benefits of visualizing issues and having the ability to plan, so you’re not just blindly stabbing at problems.”

“Anyone who has a large portfolio of properties, whether they’re a municipality, an owner of multifamily housing buildings, a school or university, or a commercial real estate developer, they are at an advantage over those who own one or two buildings, in terms of potential energy savings” says Collier.

Why?

“You’re not looking at the buildings on a building-to-building basis, but it’s more like an eco-system,” he explains. “You’re looking to the entire built environment to help you achieve your goals. You can compensate for the underperforming buildings by partnering them with net-positive, over-performing buildings that go beyond net zero and are actually able to put energy back into the system. Photovoltaics, for instance, aren’t a good fit for some structures, like an historic property, but if you also own a newer building, that might be more fitting for installing photovoltaics and then sharing the energy among properties. You can achieve your overall goal with a large portfolio in a way that an individual owner can’t.”

For Lynch, there’s been one more important benefit.

“The DPW and the rest of the city have common goals now,” she says. “We’re not all operating in our own silos. We’ve developed strong relationships across the city. People are working together, with shared goals and shared understanding of our needs.”

Chris Kelly is the director of Fifth House Public Relations in Massachusetts.