A Campus Project Packed with Extracurricular Challenges

At N.C. State University in Raleigh, a building designed around a state-of-the-art textile machine also accommodates typical office and lab tenants, but getting to the finish line wasn’t easy.

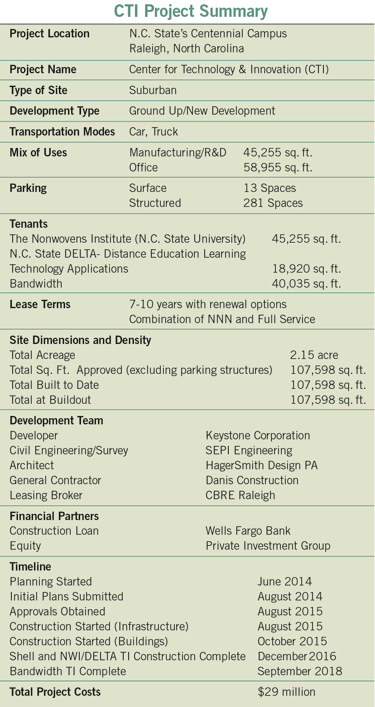

THE CENTER FOR Technology & Innovation (CTI) at N.C. State University in Raleigh, North Carolina, combines Class A offices and laboratories with an active manufacturing space. A portion of this unique mixed-use building was originally envisioned as the home for a huge, specialized machine used in nonwoven textile research and production. However, after construction commenced on the building, the machine and ground floor space were redesigned, forcing costly changes to the 107,598-square-foot facility.That was among the design, logistical and construction challenges the development team at Keystone Corp. overcame to finish the project, which includes 45,255 square feet of high bay manufacturing space on the ground floor, two levels of market office and lab space above, and a structured parking deck.

Finding a Home for a Modern-Day Loom

N.C. State needed a building to house a very large and expensive nonwoven spunbond extruder machine for the Nonwovens Institute (NWI), the world’s first accredited academic program for the interdisciplinary field of engineered fabrics. The NWI is an innovative global partnership between industry, government and academia that’s affiliated with the N.C. State College of Textiles.

This nonwoven spunbond extruder machine occupies the first floor of the Center for Technology & Innovation. It’s used by N.C. State’s Nonwovens Institute (NWI), a partnership between industry, government and academia that’s affiliated with the N.C. State College of Textiles. The machine, which is roughly 52 feet tall and 170 feet long, produces prototypes of fabrics that are used in a variety of consumer, medical and industrial applications. Photo courtesy of Monica Slaney | photographie:fourseven

The machine produces fabrics composed of polymer fibers bonded together through a variety of processes on a belt production line. Nonwoven materials are cost-efficient and prevalent in disposable hygiene and healthcare products (baby diapers, surgical gowns, cleaning pads), filtration, geotextiles, carpet backing, various insulation products and much more. The industry is growing quickly and is expected to be worth nearly $35 billion by 2022, according to research firm MarketsandMarkets.

Many large producers of nonwoven fabric, such as Proctor & Gamble, Johnson & Johnson and Mohawk, rent time on this prototype machine to develop and test new nonwoven fabrics before mass-producing them in their own factories.

The machine, which is roughly 52 feet tall and 170 feet long, requires about 60 feet of clear ceiling height space above it — more than double the 26 feet of clear height in the rest of the ground floor. The towering machine rises through all levels of the building and is separated from other areas by a heavy wall designed to prevent noise, vibrations, heat, smoke and fumes produced during manufacturing from penetrating into the rest of the building. It’s also where overhead cranes and other supporting infrastructure are housed.

The building requires more than 4.5 megawatts of power and 725 tons of cooling capacity to serve the machine and other occupants. CTI is connected to the campus chilled water loop that fuels an HVAC system more economically and reliably than a stand-alone chiller system.

The LEED Silver-certified building houses two other tenants — N.C. State DELTA (18,920 square feet on the second floor) and Bandwidth (40,035 square feet on the second and third floors). DELTA stands for Distance Education Learning Technology Applications. Its space is a consolidation of departments that previously occupied several smaller offices across campus. At CTI, DELTA is fit out with an open floor plan with manager offices in the core and open desk/work cube areas around the perimeter to maximize natural light.

Bandwidth, which occupies a portion of the second floor and the entire third floor, is a communications technology company that is representative of the kind of businesses that have contributed to the rapid growth in Raleigh and the Research Triangle Region during the past few years. It has a built-out open office layout that provides for “plug and play” and the reshuffling of departments without significant interruption to operations.

N.C. State’s Centennial Campus was chosen as the home of the CTI facility because of its proximity to the College of Textiles. The CTI site was previously a surface parking lot that the university’s long-range plan for Centennial Campus identified as a future location for a research-related building.

Located just south of the university’s main campus, Centennial Campus was established in 1984 and has since grown dramatically. It features a combination of state-funded facilities as well as buildings financed through public-private partnership (P3) structures. The CTI, as well as Keystone’s first building on campus (Keystone Science Center), are P3s.

Complex Elements Come Together

The mix of an active manufacturing facility with a more typical office/lab environment added significant complexity to the design effort. For example, the NWI industrial lab was planned to house both wet and dry labs, as was the speculative office/lab space in the upper levels.

Keystone had to start with the NWI space and design the remainder of the building around it, because it wasn’t financially feasible from a private-development perspective as a single-tenant structure. Class A offices and flexible labs are in high demand on campus from both the university and the private sector, so speculative space was a crucial component of the project.

Those upper-level areas were designed to accommodate a 50/50 mix of office and lab tenants. The top two floors feature clear heights of 12 feet, along with stout, level floor structures to handle heavy, sensitive lab equipment and significant glass to maximize views and natural light.

The loading dock and other common elements were designed to accommodate all tenants. A 16-foot-wide service corridor allows NWI to temporarily store incoming or outgoing materials without hindering other tenants from using the dock. The service corridor connects the loading dock to a freight elevator that has 48-inch-wide doors and a 4,500-pound load capacity.

DELTA and Bandwidth will typically use the loading dock for normal office deliveries. However, this portion of the building was also designed to allow for an upper-floor tenant to receive deliveries used in labs, such as bottled gas, pharmaceutical supplies, etc.

Finally, though it seems likely that N.C. State’s huge investment in this facility will make NWI a long-term tenant, Keystone had to design the ground level with enough flexibility to accommodate other uses if NWI were to move out. The two-story ceiling height can allow for an additional floor to be built in between, increasing the rentable area on the lower floors.

Zoning Complexity

As for municipal building approvals, Centennial Campus operates as an island of sorts. It is approved as a large planned development with the city of Raleigh, which has zoned the campus as primarily “Office Mixed Use” with some limitations on building height. However, the city has delegated authority for many aspects of general building plan approval to the university under N.C. State’s 1994 Physical Master Plan. That document provides a long-term vision for the types of facilities that will be built on campus and focuses on integrating institutional activities into mixed-use communities.

State-owned buildings go through North Carolina’s State Construction Office for permitting, while privately developed buildings go through the city. This site was already zoned for the proposed use, but because the building was on campus, Keystone was required to achieve university-level approvals in addition to typical site and building review by the city. Raleigh delegates authority for zoning-related items (setbacks, building height, transportation, etc.) and appearance (elevations, exterior materials, etc.) to the university. The city completes a plan review (as it relates to building codes), issues permits, completes inspections and grants occupancy. However, that is for private-sector buildings only; buildings constructed by the university are subject to State Construction Office permitting and inspections.

To add another layer of complexity, university-related tenants are often required to gain State Construction Office approval for their interior fit-out, which can add unplanned base building requirements even if the base building is not under state jurisdiction.

Keystone had already developed a building on campus with a mix of university and private tenants, so the company was able to navigate inspections and approvals without too many surprises.

About the Financing

The building was financed with a mix of equity from a small group of private investors and bank debt from Wells Fargo. The private investors are led by Keystone’s CEO, Pat Gavaghan, who is a noted alumnus of N.C. State. Several years earlier, Wells Fargo was also the lender on the 78,000-square-foot Keystone Science Center, an office/lab building similar to the CTI that’s located one block away on campus.

Two primary factors aid lender underwriting for campus projects. First, the university has sole discretion over new projects, which controls the supply of available space. Vacancy across campus has always been below 5 percent and often much lower. Second, both Keystone buildings are anchored by state entities, so there was significant pre-leasing by a credit-worthy tenant. Those factors provide stability that lenders like.

The building is owned by a Keystone-related ownership entity under a long-term ground lease with the University Endowment Fund. Keystone pays “rent” on the ground lease annually, and that rent is subject to periodic adjustments based on land valuations. Keystone plans to manage the property for as long as it owns it.

Fits and Starts

This project was unique from a construction perspective because the penalty for not delivering the building on time was much larger than just delaying rent commencement. While it was being built, there were several bumps in the road that worried all project stakeholders.

NWI was working with Reicofil, a German manufacturer of machinery used in the production of nonwoven fabrics, to design and build the nonwoven spunbond extruder. After being selected as the project developer, Keystone’s design team worked collaboratively with NWI and the Reicofil group to deliver a space that would house the machine and provide the flexibility to increase the extruder’s capacity if needed.

However, Keystone’s private development “pace” is much different than the university’s. The design and administrative approvals needed to purchase the NWI spunbond machine were finalized well after Keystone had commenced construction on the base building. That, coupled with the fluid nature of the designs for both the building and the machine, provided plenty of chances for the deal to go sideways.

Because construction began on the base building before the machine’s design was complete, the company and its investors faced the possibility of paying large, unplanned base building costs to properly accommodate the extruder. Regular Skype calls and face-to-face design meetings with Reicofil revealed necessary changes to the base building due to changing machine designs.

For example, the Reicofil team told Keystone that the total expected heat load of the extruder had increased significantly, which resulted in the potential for much more HVAC capacity. Those requests came after building steel and HVAC units had been ordered and the chilled water line was put in place. The cost to add this capacity was extraordinary. Keystone and the university were operating within budgets, and at this point in the design stage there was always the opportunity for finger pointing and claims against the other for the responsibility to bear this added cost.

Weather Issues

Time and weather were also constant nemeses throughout the project. The design process that started in June 2014 was slow and ran into the fall. Permits weren’t issued until August 2015. Starting in October 2015, heavy rains in the aftermath of Hurricane Joaquin and more unseasonably wet weather halted all site work for much of the first two months of construction. Then, early winter weather prevented completion of the site work needed to begin erection of precast concrete slabs for the parking deck. Because the weather affected most construction sites in the area, when it cleared, every project clamored to have the same subcontractor base work overtime to catch up.

The ripple effects of the weather delayed delivery of the parking structure. The base building was originally scheduled to be finished in early October 2015. It ultimately opened the last week of December. The parking deck was delayed several more weeks.

There was a silver lining to all the wet weather, however.

After Keystone made cuts that were more than 20 feet deep in portions of the slab, the finished grades were just above bedrock. A large pit under the machine that allowed for operational air flow began to fill with water as the water table rose because of all the rain. The issue wasn’t detected during Keystone’s initial geotechnical investigation, but because of the pooling water, Keystone decided to add an underground drainage system to ensure that water didn’t intrude through the slab.

Had the issue not been noticed, Keystone likely would have incurred tremendous costs to deal with it after NWI’s machine was erected.

Site Challenges

Though Centennial Campus is situated in a suburban office market, managing a construction project there is like building in an urban setting. CTI stands at the corner of Main Campus Drive and Research Drive, which is a busy intersection for bus and pedestrian traffic on campus. Keystone was required to keep these roads open during construction, despite having to excavate down as much as 20 feet in areas adjacent to those streets. Shoring in this active area was expensive, and the general contractor had to focus intensely on safety around the site.

The grade fell by more than 40 feet across the site, but Keystone utilized the steep slope to provide the high bay space that NWI required. However, the company had to fit a large building footprint of 38,850 square feet and a parking deck of 25,375 square feet on a 2.15-acre site with limited options for circulation. The College of Textiles building that’s adjacent to CTI has two loading docks, and Keystone was required to maintain full circulation for tractor trailer trucks to reach them during construction of CTI. This meant there was little flexibility for making curb cuts to accommodate egress. It also meant that Keystone had to allow clearance for those trucks to move freely under the parking deck and under the overhead bridge connecting the CTI building to the deck.

A Last-Minute Leasing Surprise

Just before base building completion, Keystone began working with a pharmaceutical company to take the space that was eventually filled by Bandwidth. That firm was in the process of gaining FDA approval for drugs used to treat various cancers. As part of this approval, the company had to show it could safely manufacture those drugs, but this highly customized manufacturing lab space had to be completed very quickly in order to maintain the approval timeline. CTI was one of the few options in the area with the laboratory capacity for such a space.

The upper levels of the Center for Technology & Innovation are occupied by office and lab space. One tenant, Bandwidth, a communications technology company, has a built-out open office layout that features a large kitchen and dining area. Photo courtesy of Keystone Corp.

Keystone held nearly constant design meetings to expedite the construction of a drug manufacturing facility that would include fitting out a large portion of the third floor to ISO 7/8 Cleanroom lab standards. The total cost of this fit-out was expected to be more than $350 per square foot. This included moving an existing 100,000-pound HVAC unit to the roof, which the building’s unique structural system could withstand. CTI was constructed with significantly more structural steel than a typical office building. It includes about 12 pounds of steel per square foot, whereas most typical office buildings are in the range of 8 to 9 pounds of steel per square foot.

Unfortunately, the drug company failed an FDA hurdle very early in construction, and all operations ceased. Its stock price sank, and Keystone had to draw on a large deposit posted by the drug company that was required upfront due to credit risks.

That deposit allowed time to re-lease the space, so Keystone began working with a large corporate tenant on campus that wanted to consolidate its R&D operations. A plan was created that provided enough room for staff and shared lab space. Financial approvals made their way through the company’s North American hierarchy, but then languished in its international headquarters.

In the meantime, Keystone fully negotiated a lease and made plans for tenant-improvement construction. However, the company’s CEO abruptly changed its long-term R&D strategy and abandoned the plan. Keystone was compensated for its time and out-of-pocket expenses, but it was forced to try to lease the remaining space for the third time.

Luckily, the space was in high demand, and a deal was made quickly with Bandwidth.

Michael Blount is executive vice president of Keystone Corp. in Raleigh. CTI was named Large Project of the Year at the 2017 NAIOP North Carolina Conference.