The Evolving Automotive Industry: Detroit Meets Silicon Valley

Electrification, artificial intelligence, autonomy and mobility services are having big impacts on the Bay Area commercial real estate market.

THE BAY AREA and Silicon Valley have long been the epicenter of the technology industry, so it is no surprise that the rapid evolutionary changes that are beginning to appear in cars, trucks and buses originated there. Even more interesting is the rapid migration of companies into the area to capitalize on the emergence of these new technologies.

Every major automotive company now has divisions located in the Bay Area, including General Motors’ Cruise automation division and the Ford Research and Innovation Center Palo Alto. Mercedes-Benz, Audi, BMW and Volkswagen have significant research and development facilities in the Bay Area, all of which are dealing with advanced automotive work that may encompass everything from electrification and increased connectivity to shared and autonomous vehicles.

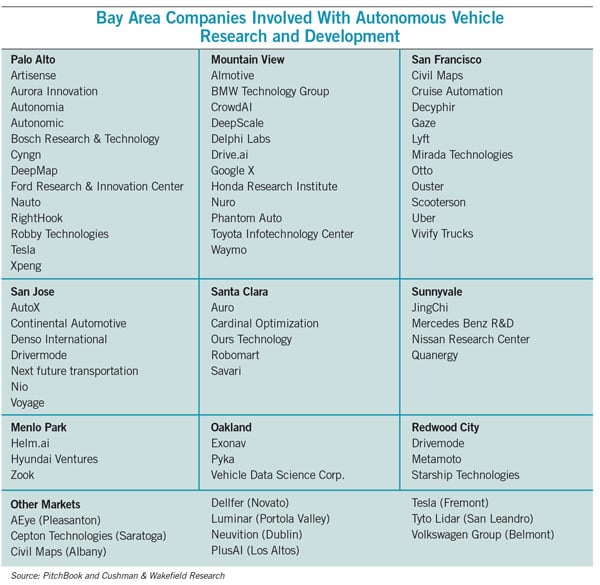

Delphi Technologies, one of the world’s largest original equipment manufacturing (OEM) suppliers, has a lab in Mountain View, while Germany’s Continental (generally thought of as a tire maker) now has a burgeoning 65,000-square-foot R&D facility in San Jose devoted to self-driving and electric powertrain technologies. These are just some of the nearly 100 automotive-oriented groups that have either set up shop in the Bay Area or spun off from other larger local groups in the last few years.

Tesla Motors, headquartered in Palo Alto, is the single largest automotive-related user of Bay Area real estate, and is by far the largest automotive-related employer there. As the first successful large-scale manufacturer of electric automobiles, Tesla has had a profound impact on the market, both as a consumer of space and a driver of new technology.

Drivers of Growth

What key trends are driving growth in the automotive industry, and how are they impacting Bay Area real estate markets? Autonomy, connectivity, electrification and sharing (which includes mobility services), often referred to as ACES, comprise the four broad categories occupying space in the advanced automotive community. These industries, both separately and in connected ways, underscore the westward shift of R&D in automotive technologies from Detroit to the Bay Area, and indeed from automotive manufacturing centers around the world. All of these groups occupy space in the Bay Area real estate markets.

Autonomy is being driven by some of the largest Bay Area tech companies. These include Waymo’s parent, Google; Mobileye, recently acquired by Intel Corporation; and Uber, through its Advanced Technology Group, the self-driving truck unit formerly known as Otto. Most recently, Lyft announced a major R&D center in Palo Alto that reportedly includes partners such as Waymo, nuTonomy, Jaguar/Land Rover and GM, taking a more “open platform” approach. Recently they upped the ante by announcing a partnership to manufacture systems with Canadian auto parts powerhouse Magna. Approximately 60 companies in the Bay Area are now focused exclusively on autonomous vehicle development.

A prime example is Velodyne, the leader in Lidar (light detection and ranging), the laser sensing technology that enables autonomous vehicles to “see” the roadway and obstacles around them. These sensors, commonly attached to car roofs, look like spinning “fried chicken buckets,” and are one of the key components in developing vehicle autonomy. The majority of current autonomous vehicle development programs use the Velodyne system. The company recently purchased a 200,000-square-foot manufacturing building in San Jose. Although the new building has enabled Velodyne to significantly increase its capacity, customers still face at least a six-month back- log for deliveries of this critical component.

The very idea of autonomy has fundamentally changed how the automotive business views itself. The dialogue within automotive circles has evolved rapidly from autonomy being characterized as an “unlikely fringe element” to its becoming an accepted mandate. Competition is being fueled in part by government regulators, insurance companies and health care experts, all of whom have given the autonomous vehicle, which could save tens of thousands of lives annually, a thumbs-up. Industry leaders and Washington lawmakers are now seeking to roll out level 4 and 5 autonomy (fully autonomous, with or without traditional controls) as fast as possible.

The debate about when and how these technologies will become commonplace continues. GM has recently jumped ahead of Ford, announcing that it plans to introduce a fully automated ride-sharing service similar to Uber by 2019. Ford has promised consumers a fully autonomous vehicle by 2021. It wasn’t long ago that the automotive industry was still grappling with the idea that many of tomorrow’s cars may not have steering wheels at all, and that many future car buyers would simply opt out of direct ownership altogether. Now, they appear to be accelerating that very change.

To illustrate the speed with which all of this is occurring, Waymo received approval from city officials to deploy completely driverless Chrysler Pacificas on the streets of Chandler, Arizona, in February 2018, with vehicles picking up and dropping off passengers in a pilot program. That same month, the California Department of Motor Vehicles announced that it will permit testing of fully autonomous vehicles, without safety drivers, on select highways and streets.

Only a few weeks later, Uber halted tests of its autonomous vehicles throughout the U.S. and Canada after a Volvo XC90 operating in autonomous mode struck and killed a pedestrian in Tempe, Arizona, in March 2018. While the investigation into that incident is ongoing, other groups, including Waymo, continue their road tests in Arizona and elsewhere.

Connectivity is one of the least understood aspects of the new age of mobility. Yet it will be critical if autonomy is to take hold in both urban and rural settings. Think about the importance of cell towers. The advent of level 4 and 5 autonomy cannot take place without the widespread integration of new 5G communication technology (fifth-generation wireless systems).

Autonomy is as much about vehicles being able to communicate with one another as it is about self-driving features in the vehicle itself. Connectivity technologies have historically been headquartered in Silicon Valley. These industries, including companies such as Apple, Broadcom and Samsung, already command a huge presence in the market. These legacy companies occupy many millions of square feet in the Bay Area.

Electrification and the development of electric vehicles is occurring globally, but Tesla has led the way in delivering fully electric automobiles on a large scale. Lucid Motors in Menlo Park recently leased an additional 126,700 square feet in Newark, directly across the highway from Tesla’s new 230,000-square-foot Fremont office complex. As Lucid prepares to bring its high-end electric cars to market, other more familiar names have set up operations in the Bay Area to develop electric vehicles and drivetrains. These include Porsche, Volvo and Hyundai, to name just a few.

Sharing technology and mobility services are the focus of giants Uber and Lyft , but myriad other aspects of this new trend are being addressed with R&D funded by the major automakers, and much of that work is being done in the Bay Area. Researchers are attempting to get a handle on how people will use and access vehicles in the future, and automakers are trying to figure out how to target future sales of automobiles. On the other end of the sharing spectrum, the likes of Ford Bike and Lime Bike are attempting to solve “last-mile” transportation gaps with fleets of high-tech bicycles that can be rented and accessed via smartphone apps.

From NUMMI to Tesla

The 2010 closure of the New United Motors Manufacturing Inc. plant (a joint venture between GM and Toyota) in Fremont, which was California’s last automotive assembly plant, left a 5.3 million-square-foot hole in the East Bay industrial market. By 2009, the region had already lost 3,000 jobs at the plant and approximately 4,000 related supplier jobs. Real estate experts and economists predicted that this was the end of automotive production in the Golden State. They spoke too soon.

Tesla Motors’ purchase of the plant the same year it closed triggered a remarkable turnaround that today includes 6,000 assembly jobs, 10,000 additional administrative and R&D jobs, and thousands of supply chain jobs in the broader Tesla ecosystem. The current 5.3 million-square-foot plant is expected to grow to 10 million square feet on nearby land owned by Tesla, whose expansion plans have received approvals from the city of Fremont.

In surrounding submarkets, Tesla and its major suppliers occupy some 3.3 million square feet of additional space. Tesla is far and away the single largest user of industrial real estate in the Bay Area. With production of the low-cost Model 3 ramping up, deliveries are projected to increase fivefold to over 500,000 units annually by the end of 2018. By most accounts, the effect of Tesla’s already significant presence has just begun. While significant development has occurred over the last several years, vacancy rates remain extremely low.

Market Focus

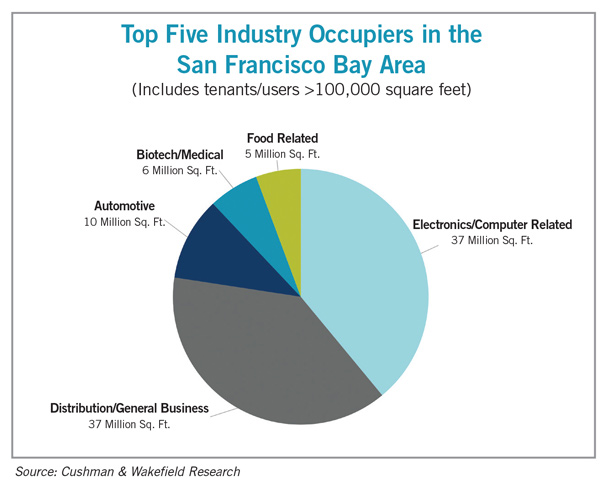

How is growth in these related industries impacting the Bay Area market? The largest impact is being felt in the East Bay industrial markets, where the “Tesla effect” is most pronounced. Taken as a whole, the overall impact of the automotive space is impressive and growing. San Francisco, primarily an office market, has over 1.5 million square feet of office space currently occupied by automotive-related companies, including Uber, Lyft, Cruise and Otto. Within the Peninsula market, which includes Palo Alto and Menlo Park, R&D space related to advanced automotive groups has a significant presence of roughly 700,000 square feet. Major blocks of space have been consumed by automotive uses in nearly every city in the Bay Area, putting stress on an already tight market.

Advanced Manufacturing

“Advanced manufacturing” is a catch-phrase used to describe large-footprint industrial buildings intended to house high-tech, worker-intensive industries. With early entrants in Tesla’s supply chain such as Futuris, SAS Automotive and Draexlmaier, all of whom supply interior components and employ large numbers of workers, city planning departments throughout the East Bay are using the critical shortage of developable industrial land to demand that traditional warehouses make way for the higher-image, heavily powered facilities with more parking that advanced manufacturing industries prefer. Theoretically, these facilities will enable the companies occupying them to create more and higher-paying jobs.

In many submarkets, jurisdictions are now requiring conditional use permits (CUPs, also known as special use permits) for standard warehouse uses and are imposing these restrictions not just on new developments, but also on older, existing facilities and existing tenants. It can take several months for a company to apply and receive approval for a CUP, which significantly increases transaction times. These factors can negatively impact properties and entire submarkets that require CUPs, since many tenants will opt to locate in nearby markets that do not require CUPs. On the other hand, manufacturing uses that can demonstrate potentially higher employment will not be required to get CUPs. Cities that are hoping to increase their long-term employment base by requiring CUPs for standard uses are taking a gamble with their core warehouse base.

One developer that has embraced these trends is Overton Moore Properties, which has parlayed its early success in accommodating advanced manufacturing companies into the start of construction on the largest new industrial park project now underway in the Bay Area. Pacific Commons South, also known as PCS, will include 10 buildings with a total of 1.7 million square feet, primarily advanced manufacturing space. Construction began in April 2018 and PCS is expected to be completed by the end of the year. The Tesla plant is less than two miles away.

Immediately adjacent to PCS, Conor Commercial Real Estate is building an 817,000-square-foot warehouse development known as Pacific Commons Industrial Center. Soil preparation was underway in spring 2018; the project is expected to be completed in spring 2019. This will be the single largest spec industrial building ever constructed in the East Bay. It will accommodate either warehouse or manufacturing uses.

What’s Next?

Key elements of the advanced automotive industry are still shaking out. The industry has rapidly embraced changes and major automotive manufacturers have moved key departments to Silicon Valley. Ford’s new CEO, Jim Hackett, is one example of this trend; he was tapped to lead the company after running its smart mobility division in Palo Alto. Hackett was recently quoted as saying, “Being frozen in the past is really a death sentence. We’re looking at things that we never would have imagined 10 years ago.” The emphasis at Ford seems clear.

While the center of gravity for automotive research has indeed shifted west, the future of the automotive industry unfolding in the Bay Area is similar to the evolution of the personal computer industry. With a culture of innovation, the availability of venture capital money and two top-tier universities – the University of California, Berkeley, and Stanford University – providing intellectual capital, the Bay Area is fertile ground for promoting change. However, the cost of operating in the Bay Area markets remains extraordinarily high and is trending even higher. These costs will likely make large-scale manufacturing in these markets a challenge.

This paradigm was also true when large-scale computer manufacturing began and was then outsourced to more inexpensive markets. Thus, automotive technology developed in the Bay Area will likely be integrated into existing automotive manufacturing strongholds as soon as it is approved. Recent trends do not point to the end of Detroit’s dominance. Rather, they suggest that technology born in the Bay Area will enhance and fortify one of America’s great industries, making it stronger and more competitive. Bay Area real estate markets will continue to accommodate new technological advances and Tesla’s burgeoning footprint, but local cities must remain creative and flexible if the area is to keep up with the demand for space.

Remarkable transformations are taking place in the automotive industries, and those changes will impact personal transportation, trucking and other ground transportation, and much more. The impacts of change in the automotive industry have already had a major impact on the real estate market in the Bay Area, and savvy developers are factoring this increased demand into their office, R&D and industrial projects.

Michael E. Karp (michael.karp@cushwake.com) is a managing director with Cushman & Wakefield and a former member of the board of NAIOP San Francisco.