Best Practices in Developing Skilled Nursing Facilities

An Ohio-based developer of these specialized properties describes how it is capitalizing on growing opportunities as well as evolving market trends.

AN AGING POPULATION and medical advances that are extending the average person’s life expectancy are increasing the need for skilled nursing facilities. Developers are responding by gearing up to build more of these projects to meet the expected need. One such company, Premier Health Care Management, a Cincinnati-based nursing home developer and operator, plans to double in size in the next three years by expanding its total number of beds from 700 to 1,200 through building renovation, expansion and ground-up construction.

Premier’s in-house architectural team, PHCM Construction Inc., is currently working on five nursing home development projects with a combined construction value near $100 million. All are geared toward capitalizing on market trends that include residents’ desire for private rooms and more amenities. These trends, along with variables such as site conditions, occupancy codes and availability of financing, are among the primary challenges faced by most senior living development projects.

Grade fluctuations presented serious challenges to the development of an 85,000-square-foot addition to Forest Hills Care Center in Anderson Township, Ohio. Photo courtesy of Michael Adkins, PHCM Construction Inc.

The examples below demonstrate how many of these challenges can be transformed into opportunities that will contribute to a project’s flexibility, cash flow and long-term success.

More Private Rooms

Completed in January 2018, Social Row Transitional Care Center is a 100-bed, 98,000-square-foot skilled nursing and post-acute (short-term rehab) care facility located in Washington Township, Ohio, between Cincinnati and Dayton. One of Premier’s primary challenges with this project centered on producing a building that offers as many private rooms as possible while also considering the impact of the building size on nursing home operations.

“Residents today are seeking the best possible health care available, and that includes the comfort of a private room. We are doing our best to provide this option, but it’s also important to design a building that enables our staff to oversee all resident activity in a seamless way. As the buildings grow in size to accommodate resident needs, health care operations become one of our biggest challenges, one that we must always balance carefully,” says Harold Sosna, president of Premier Health Care Management.

To meet this challenge, the company’s design team makes many calculated decisions regarding the location of nurses stations, linen closets, storage rooms and administrative offices. All resident rooms are within visual sight lines of at least one nurses station. Linen closets are strategically located near resident rooms, so that nurses and other staff don’t have to walk far to replenish rooms with clean linens. Administrative offices are positioned in a separate part of the building, away from resident rooms.

Varying Levels of Care

A second challenge that all skilled nursing facilities face involves how to design a building that can accommodate residents who require varying levels of care. Social Row is currently set up to receive both post-acute and long-term care patients. “Sometimes we may have a majority of short-term residents, while at other times the opposite may be true,” says Sosna. To plan for this reality, best-in-class designs feature patient rooms, dining facilities, serveries (counters, service hatches or rooms from which food is served), lounges and nourishment centers (combination storage and food service units) that can accommodate both types of residents at any given time.

Social Row Transitional Care Center, shown here under construction in August 2017, features protected courtyards as well as rooftop solar panels, which were financed in part through PACE financing. Photo courtesy of Michael Adkins, PHCM Construction Inc.

In addition to designing efficient, flexible buildings, Premier also aims to create stimulating environments for residents by incorporating plenty of amenity spaces. Sosna says, “We want our residents to have a meaningful experience while at Social Row and I believe our amenity spaces will enrich the rehabilitation process.”

Leveraging some concepts found throughout the company’s seven other facilities, Social Row features a pub, a gift shop, a beauty shop, a soda shop and a 16-seat movie theater available to residents and visiting family members. It also has a 1,200-square-foot activities hall where residents can participate in a variety of social activities and events, as well as additional lounges, courtyards and sitting areas for residents.

Ohio state code requires skilled nursing facilities to have a minimum of 25 square feet of activity space and 25 square feet of dining space per resident. Sosna believes it’s important to go above and beyond those minimum requirements when possible, especially if doing so can contribute to greater patient satisfaction. To that end, Social Row’s activity and dining spaces add up to almost 12,900 square feet, or about 129 square feet per resident, more than double the minimum required.

Site and Code Issues

An 85,000-square-foot addition to Premier’s existing Forest Hills Care Center in Anderson Township, east of Cincinnati, offers another example of a challenge that has presented additional opportunities. The new building will add 30 private skilled nursing care rooms, 24 apartment-style assisted living units and a new physical therapy gym. When the $15 million construction project is completed in summer 2018, the facility will have grown to 151,000 square feet.

The existing facility serves 87 residents, who require a combination of short-term and long-term skilled nursing care, in a combination of private and semiprivate rooms. From a development standpoint, one of the biggest challenges Premier has faced with this project centers around site grading conditions. Significant grade fluctuations in the land directly adjacent to the existing structure required the developer to design the addition as a three-story building rather than a typical single-floor facility.

Because the new building will house skilled nursing, assisted living and physical therapy facilities, the developer needed to consider code requirements for both I-2 (Skilled Nursing, Physical Therapy) and I-1 (Assisted Living) occupancy. The building design must, for example, provide proper fire separations.

For a single-story building, this would be accomplished by simply designing a two-hour fire wall wherever the skilled nursing/physical therapy units connect to the assisted living units. The challenging site conditions, however, required a three-story addition in which the third floor would serve as the connection point to one of the existing building’s skilled nursing units. From an operational standpoint, this meant designers had to place the new skilled nursing care unit on the third floor and situate the assisted living (AL) unit directly below, on the second floor. The physical therapy (PT) facility will therefore be located on the bottom floor.

With these operational requirements and design constraints in mind, designers separated the skilled nursing and assisted living floors with a two-hour assembly between the floors in order to abide by the multiple occupancy codes. (The same scenario exists between the AL and PT floors.) However, to maintain that two-hour separation universally, the structural components needed the two-hour fire rating as well. After careful collaboration and research, Premier chose a C-joist structural assembly using Gyp-Crete floor underlayment and gypsum wallboard. “This was the first time we faced a scenario like this involving a multistory building with I-2 above and below an I-1 occupancy,” says Alex Hewitt, project manager for Premier.

While this scenario has presented challenges, it also sparked a major opportunity. Placing the 3,000-square-foot physical therapy gym on its own floor at grade level allowed the design team to include a dedicated exterior door for the gym, which leads out to a new parking lot. That separate exterior door has enabled Forest Hills to pursue an additional revenue stream by providing outpatient PT services in addition to those provided to live-in residents, who will be able to access the PT area from within the building.

Construction Financing

Financing remains a critical component for any developer. Premier typically finances its construction projects through traditional bank loans with a locked-in interest rate. While that continues to be the prevailing approach, Sosna and his team have recently embarked on projects that also incorporate Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) financing.

PACE is private capital in 99.9 percent of cases – the exception being port authorities in states like Ohio – attached directly to a privately owned building, meaning that the PACE loan conveys with the building if it is sold. The capital is then repaid by the owner through an assessment on property taxes over a 15- or 30-year period. PACE financing is repaid through property taxes, using the same type of special improvement district financing that applies to tax increment financing districts (TIFs).

PACE funds typically finance energy-efficiency measures leveraged as part of the construction project, such as LED lighting, more efficient HVAC systems, solar panels and so forth. The PACE loan enables developers to install more expensive energy-efficient equipment upfront and then pay back the loan from net gains resulting from lower energy costs.

Premier completed its first PACE deal – the second in Ohio – for Social Row, and plans to continue to use PACE to complement traditional financing wherever possible. Sosna sees PACE financing as a great opportunity for all parties involved, noting, “PACE helps me get the capital I need upfront while the municipalities can earn additional property tax revenue – and, in the process, we build an energy-efficient building that is less expensive for us to operate.”

The Future

Looking ahead, it is clear that the need for these types of facilities will continue to grow as the population of North America ages. Developers who choose to enter this asset class must understand the many challenges involved in building and operating safe, comfortable, efficient and flexible skilled nursing facilities, many of which may also provide short-term rehab and PT services. Developer-operators who aim to deliver the best possible health care to their residents will need to pay careful attention to every detail.

Greg Lazaroff (glazaroff@premierhcm.com) is director of business development at PHCM Construction Inc.

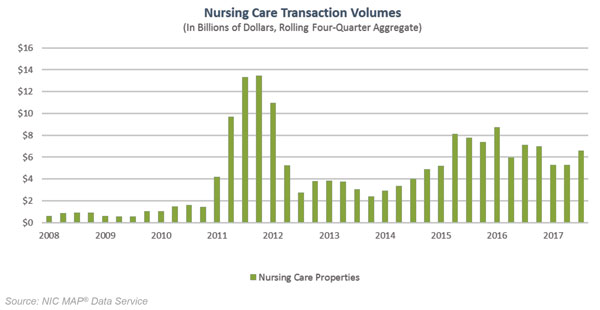

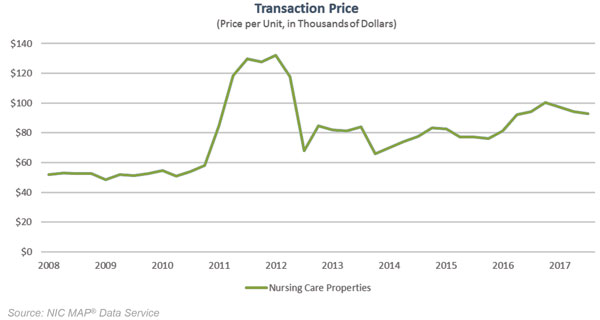

Investing in Skilled Nursing PropertiesWhile recent headlines have highlighted a number of businesses that are modifying their investment strategies related to skilled nursing properties, a number of other investors are doubling down or entering the space in less conventional ways. Investor interest remains relatively strong, with $3.5 billion in transactions, comprising 439 properties, changing hands in the third quarter of 2017.  Since 2008, only three other quarterly periods experienced stronger dollar volume. On a four-quarter rolling basis, there were $6.6 billion of deals done, inclusive of 777 transactions. Meanwhile, pricing remains relatively strong. It averaged $93,000 per bed in the third quarter, close to its recent high in late 2016 of $100,000 per bed, based on a four-quarter moving average. Investors must consider an array of options for financing, selling and purchasing skilled nursing properties. On the positive side, of course, are demographics, as large numbers of baby boomers and their parents continue to age. Long-term skilled nursing care and short-term rehabilitation services both stand to benefit from this significant trend. The slower implementation of new value-based care and bundle-based payment models by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in 2018 should also provide near-term support to operators of skilled nursing properties. Bundled payment models, however, with their greater emphasis on health outcomes and less focus on fee-for-service options, will present a longer-term test for the sector.  Other challenges facing the sector include labor shortages and rising wage rates, shifting Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement models, more acutely ill patients, aging buildings, narrowing of post-acute provider networks and rising competition from home health and other sectors. The skilled nursing sector also faces continued occupancy reductions resulting from shorter lengths of stay, as well as some daily rate pressures through the greater penetration of Medicare Advantage (MA) plans, which can affect operators’ profitability. NIC’s Skilled Nursing Data Report for the second quarter of 2017 shows that the share of Medicare managed plans continues to rise while revenue per patient day (RPPD) continues to fall, ending the second quarter at $437 per day, down from more than $490 per day in 2012. For some capital providers, investing more intensely in operations or big data systems, such as electronic health record (EHR) systems, that create economies of scale and nurture new business opportunities and partnerships is a strong way forward. For others, investing in ancillary and home care services seems more compelling. Meanwhile strong operators are acknowledging today’s challenges and working to maintain and create the most cost-effective care-intensive option possible for both today’s aging seniors in need of long-term care as well as their children, who often need short-term care and rehab services while recovering from joint replacements and other afflictions common to baby boomers. By Beth Burnham Mace, chief economist, National Investment Center for Seniors Housing & Care (NIC), bmace@nic.org |