Cookie Cutter Environmental Diligence Doesn't Cut It Anymore

It must be customized for each property.

ATTORNEYS WHO provide environmental support for commercial real estate law practices often work with a wide range of buyers, sellers and lenders. Each of these clients has its own appetite for – and way of grappling with – the environmental liability risk that its deal presents.

Tom Mounteer

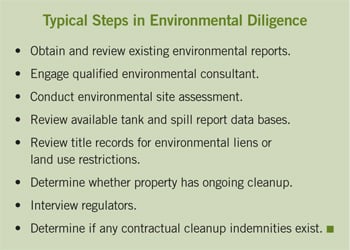

Present-day environmental diligence is shaped chiefly by the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), the federal statute commonly known as the Superfund law. Under that law, purchasers of properties on which hazardous substances have been released can avoid liability for those releases if they make “all appropriate inquiry” before their purchase and exercise “appropriate care” afterward. Federal rules define both concepts.

Within this legal framework, however, how environmental diligence is carried out depends on the specific facts of the affected property and the parties’ risk tolerance. A few examples illustrate how environmental diligence really has to be “tailor made” for each deal.

Industrial Site Redevelopment

One client’s 2017 project illustrates exactly the type of redevelopment the exemption from Superfund liability was intended to encourage. The client planned to invest with a developer that intended to demolish about a dozen buildings formerly operated by a bankrupt stainless steel rolling mill and replace them with a very large (more than 250,000-square-foot) distribution center.

This type of redevelopment is a fairly typical beneficial reuse for sites with contaminated soils. Essentially slab-on-grade buildings cap and cover the soil, eliminating exposure and preventing precipitation from leaching soil contaminants into groundwater.

At the time the client was being asked to make its investment, the site’s cleanup hadn’t been completed. The last operator of the stainless steel mill had committed a lump sum toward the cleanup. The money ran out before the cleanup was completed, and the mill stopped operating. The attorneys’ job was to determine what additional remediation the client’s development partner would have to undertake, at what cost, so that the site could be safely used as a distribution center. After investigation, the client made the investment, and its development partner acquired the property.

Different Tolerances for Risk

Another client asked for assistance in a less typical site reuse: the redevelopment of an actual Superfund site – one that had been placed on the federal National Priorities List of 1,300 sites in need of federal attention – for residences.

Beginning in the early 1970s, the site had been used for semiconductor fabrication. The prior operator stored chlorinated solvents used for cleaning and degreasing in more than 20 underground storage tanks, which had leaked into the ground over the years.

In this instance, the seller had addressed the site’s environmental condition under the supervision of government regulators, who had approved the site’s reuse for residential purposes, subject to a number of environmental land use restrictions. The attorneys’ job, then, was to help the client understand those restrictions and how to abide by them.

As long as it could get comfortable with the costs of complying with the environmental land use restrictions, this client was willing to accept the risk. Another client, who was buying a hotel property, was more tentative.

Preliminary diligence indicated that a service station, with underground fuel storage tanks, operated on the northwest corner of the hotel property. The best guess was that the fuel storage tanks had been removed sometime between the late 1960s, when the service station closed, and the mid-1970s, when the hotel was developed. Unfortunately, no reports were available documenting the tanks’ removal. Even with the passage of decades, the client found the risk too great to be ignored.

One preferred approach would have been to escrow a portion of the purchase price to allow an investigation – and remediation, if one were deemed necessary – to unfold systematically after closing. The parties didn’t want to wait for that.

Instead, the client engaged a consultant to collect soil and groundwater samples. The client’s obligation to close was conditioned on the results not triggering an obligation to report a spill to a government agency. Attorneys feared that the type of very limited detection sampling that could be carried out in short order would provide the parties with too little information to help them resolve the matter. They therefore proposed an escrow that would allow a more systematic investigation after the closing.

Fortunately, very low-level petroleum residuals were detected. The parties agreed to accept regulators’ fairly informal determination that, given the concentrations of contaminants detected, there was no need for further investigation. The land sale closed.

Shifting Perspectives

One final example shows how a client might have to shift its perspective over time.

A few years ago, attorneys helped a client get comfortable with the environmental condition of an industrial park that had been developed on the site of a former aerospace manufacturing facility. The aerospace manufacturing operations had left a residue of solvents in the soil and groundwater. A prior owner had treated the groundwater for decades, under the supervision of a state agency, but had not yet achieved its cleanup objective.

Attorneys reviewed voluminous reports detailing the characterization of the groundwater contamination plume and the nature and status of the cleanup. A particular concern was that there be no risk of indoor air quality problems from solvents volatilizing from the groundwater into the site’s buildings. Attorneys also assessed the strength of the indemnity to be assigned to their client.

A prior owner had retained the obligation to address groundwater conditions under governmental supervision. The prior owner’s retention of responsibility was set out in a contract from which subsequent owners could benefit. Based on the information that was available on the groundwater remediation, and the prior owner’s retention of responsibility for it, the sale went through.

More recently, this client began to think about selling some of the tenanted buildings as well as some lots in the undeveloped areas of the industrial park. The client provided a sketch indicating potential development sites. A few of the sites were very close to areas where groundwater cleanup objectives hadn’t yet been attained. The question this raised was whether what was an entirely reasonable cleanup approach on an industrial park-wide basis would be sufficient to address potential purchasers’ concerns.

The industrial park, spanning hundreds of acres, had many groundwater monitoring wells. Any given development site, however, might have just one well, or perhaps none. The attorneys’ hunch was that, when the client attempted to sell individual development sites, particularly those sites close to wells in which groundwater hadn’t yet met the cleanup objective, prospective purchasers would insist on more sampling locations on the property they were considering buying.

Attorneys suggested that the client design and implement its own additional investigation of potential development sites. The client could design the investigations in accordance with good commercial practice and control the process. Then, when the owner marketed the lots, it would have effectively anticipated purchasers’ likely concerns. The owner could produce data indicating either that the parcel’s groundwater met regulatory cleanup standards or what additional work would be involved to achieve those standards.

The client, perhaps not surprisingly, decided to wait until it has some interested buyers before taking on that work. Because the client doesn’t expect to market these development sites for several years, the results of this plan are as yet uncertain. What is clear is that the attorneys’ advice has helped the client shift its perspective to the changed circumstances.

By Tom Mounteer, partner, Paul Hastings LLP, Washington, D.C., and professor, George Washington University Law School, tommounteer@paulhastings.com