Retrofitting Tysons: From Edge City to Walkable Urban Place

The largest and best-known “edge city” in the U.S. is being transformed into a more walkable urban center.

THE DEFINING REAL estate book of the late 20th century was “Edge City: Life on the New Frontier.” Written by Washington Post reporter Joel Garreau and published in 1991, the book chronicled the explosion of “drivable sub-urban” development and described “the most radical change in a century in how we build our world.” Edge cities are typically freeway-hugging agglomerations of regional malls, business parks, hotels and the occasional rental apartment complex. They are dependent on cars and trucks as their primary or only transportation option. And they are where the vast majority of economic growth and substantial real estate development occurred in the late 20th century U.S.

Garreau’s model edge city was Tysons Corner in northern Virginia, an area set near the intersection of two major limited access highways, the Capital Beltway (Interstate 495) and the Dulles Access Road (Route 267). Later renamed simply Tysons, it was characterized by mid- and high-rise office buildings and two regional malls, surrounded by acres of surface parking lots.

Tysons in 1989, when the book “Edge City” was published. The Dulles Access Highway (Route 267) is in the upper right corner and the Capital Beltway (I-495) is in the foreground. The Tysons Corner Center shopping mall is on the left; the then-new Tysons Galleria is at the center. Image provided by the Tysons Partnership

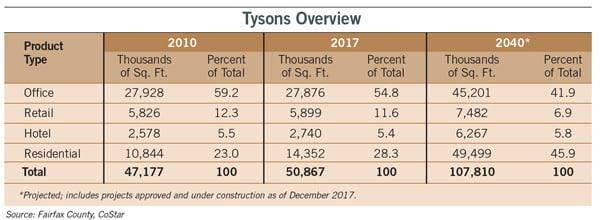

Tysons has been the largest edge city in the U.S. since the 1980s. In that decade it added on average 1.3 million square feet of new office space per year, as well as retail space, luxury hotels and apartments. Coming out of the Great Recession in 2010, Tysons had a total of 27 million square feet of office space as well as 20 million square feet of retail, hotel and residential space spread over 2,400 acres. That year, Tysons was the 13th largest “downtown” in the country, in terms of office space. With as much office space as the downtowns of Denver and Pittsburgh, Tysons housed nearly 100,000 jobs and a population of 17,000. It was larger than Perimeter Center in metro Atlanta, Chicago’s Schaumburg, Houston’s Galleria/Post Oak, Los Angeles’ Costa Mesa and Seattle’s Bellevue.

Yet Tysons also had some of the nation’s worst traffic jams, was hostile to pedestrians and had limited cultural offerings. And it was approaching full buildout under existing zoning. By the early 21st century, it also had competition from a place that offered something it fundamentally did not have: walkable urban vitality.

The Rosslyn-Ballston (R-B) Corridor in nearby Arlington, Virginia, immediately across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., had been a competitor to Tysons. During the go-go days of the 1980s, Tysons was absorbing over twice as much office space annually as the R-B Corridor. However, the R-B Corridor was then at the start of a transformation into the national model of the urbanizing suburb. Starting in the 1970s, Arlington County had based its urban plan for the R-B Corridor around five then new Metrorail stations and encouraged high-density, mixed-use zoning in urban clusters within walking distance of each station.

In sharp contrast to Tysons’ drivable sub-urbanism, the R-B Corridor offered walkable urbanism. This development model is five to 30 times denser than traditional suburban development. It offers multiple transportation options, including transit, bikes and walking, in addition to cars and trucks. And it features a mix of product types – typically office, retail and residential – as well as parks and other public spaces, plus 24/7 place management, all within about a 3,000-foot (half-mile) radius.

During the 1990s and the 2000-2006 real estate cycles, Tysons and the R-B Corridor grew at exactly the same rate of office absorption annually and had comparable office rents, about $25 per square foot. There was a standoff between drivable sub-urban Tysons and walkable urban R-B Corridor during those cycles.

Tysons Loses Market Share

During the current real estate cycle (from 2010 to the present), however, Tysons grew at only half the rate of the R-B Corridor in terms of new office space delivered. Its net office absorption was even worse; Tysons was losing 100,000 square feet annually. The R-B Corridor achieved an average office rent of $41 per square foot, compared to $31 in Tysons, a 32 percent premium.

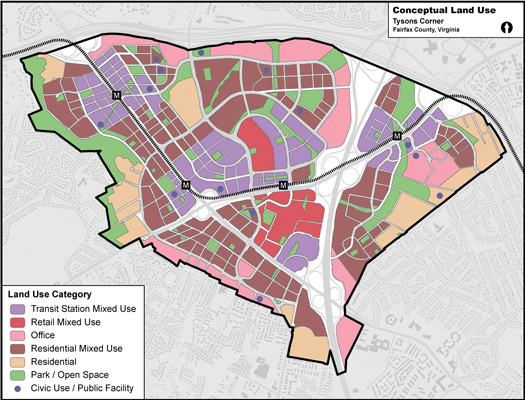

Fairfax County’s Tysons conceptual land use map focuses on accommodating mixed-use development near the area’s four Metrorail stations. Fairfax County Department of Planning and Zoning

The valuation premium was even higher, since drivable sub-urban cap rates are in the range of 5 to 7 percent versus 4 to 5 percent for walkable urban office product, adding an additional 30 to 40 percent valuation per square foot premium. The relative loss of market share and value was naturally troubling for Tysons’ property owners and developers.

In addition, Tysons was not well positioned for the major new development product of the post-Great Recession market: rental housing. Most 21st century renters did not want to live in a sterile, drivable sub-urban location like Tysons; they wanted a hip, walkable urban place like the R-B Corridor. The R-B Corridor added 1,200 apartment units per year from 2010 to 2014, versus about 370 units per year in Tysons.

These lagging office and residential rental absorption trends for Tysons came as most developers and investors in metropolitan Washington real estate were beginning to realize that the late 20th century approach to development was losing favor. Walkable urban places were rapidly becoming more popular and more financially successful in response to pent-up demand.

Back to the Future

The market was shifting “back to the future.” Developers were once again building walkable urban places, something they had not done in a century. And the focus of that development was confined to much smaller areas. Since walking distance has been fixed for thousands of years at about a half mile, this limits the size of a walkable urban place to between 100 and 400 acres. The R-B Corridor has five walkable urban places totaling 1,100 acres, or an average of 220 acres each.

“Core Values: Why American Companies Are Moving Downtown,” a 2016 report published by Smart Growth America in partnership with Cushman & Wakefield and The George Washington University, demonstrated office tenants’ growing demand for walkable urban places. Researchers surveyed over 500 corporations that had moved to these places and learned that the No. 1 reason they had done so was to attract talented young millennial workers. To be a 21st century knowledge-based, creative class company requires being located in a walkable urban place.

The growing demand for walkable urbanism, among other factors, lead the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors to establish the Tysons Land Use Task Force in 2005. Another major catalyst for the establishment of the task force was the planned construction of Metrorail’s new Silver Line, which was to add four new stations in Tysons. Comprised of citizens, planners, landowners and businesses in and around Tysons, the task force’s mission was to:

- Promote more mixed-use development.

- Better facilitate transit-oriented development (TOD).

- Enhance pedestrian connections throughout Tysons.

- Increase the residential component of the density mix.

- Improve Tysons’ functionality.

- Provide for amenities and aesthetics, such as public spaces, public art and parks.

The head of the task force was Clark Tyler, a neighborhood leader who had lived near Tysons for 50 years. A longtime observer of Tysons, he saw it as “the blob that ate Northern Virginia.” Yet he felt there was a model Tysons could follow nearby: the R-B Corridor.

Tyler and the task force studied how the R-B Corridor had evolved, following smart growth principles of high-density, walkable urban development clustered around its five Metrorail stations. Two things stood out:

- In the late 1980s, 11 percent of Arlington County’s land mass consisted of land zoned for walkable urban development, and that land generated 20 percent of its tax revenues. By 2010, more than 50 percent of the county’s tax revenues came from this up-zoned and redeveloped land.

- The main arterials serving the corridor’s five walkable urban places, which experienced a tripling of square footage since the 1980s, actually saw their traffic counts decline in absolute terms. All of the growth was accommodated by increased transit, biking and walking.

Tyler and the task force also discovered from the R-B Corridor that high-density mixed-use development within walking distance of single-family housing improved the quality of life in the surrounding neighborhoods. Allowing Tysons to evolve into a much denser, more walkable urban place, as the county’s comprehensive plan envisioned, could offer residents of surrounding neighborhoods the best of both worlds: a suburban lifestyle within walking distance of restaurants, transit, jobs and urban vitality.

Plan Approved

After an extensive community engagement process, including 300 meetings, economic and fiscal impact analyses, land use planning, and review and approval by both the task force and the Fairfax County Planning Commission, the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors approved the Tysons rezoning and urban plan amendment to the county’s comprehensive plan on June 22, 2010. The plan update calls for 75 percent of all new development in Tysons to be located within a half-mile walk of a Metrorail station.

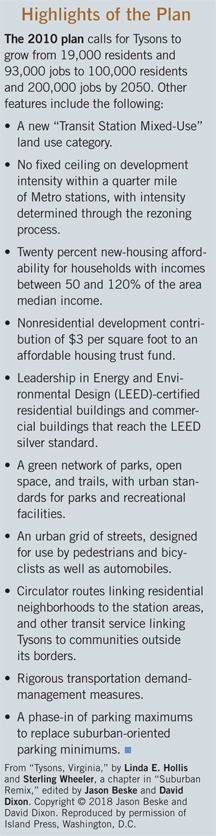

By 2050, Tysons is projected to have twice as many jobs (200,000) and five times as many residents (100,000) as it did in 2010, resulting in a jobs/housing balance of two jobs for every resident, as opposed to a 6:1 ratio in 2010. Tysons will also be more environmentally sustainable, with restored streams; a green network of public parks, open spaces and trails; and green buildings.

A redesigned transportation system will include circulator routes, community shuttles, feeder bus service and vastly improved pedestrian and bicycle routes and connections. The new comprehensive plan also called for the establishment of the Tysons Partnership, a nonprofit organization of property owners originally empowered to engage in transportation management, which has broadened its responsibilities tremendously, as discussed below.

All of this required substantial up-zoning. The new comprehensive plan allows for a tripling of the square footage existing in 2010, with up to 150 million square feet estimated to be on the ground around 2050. It assumed that much of this new development would be spurred by the four Metrorail stations, which opened in 2014. The plan and the Metrorail opening did indeed spark an explosion of rental housing deliveries. In the two years after the Silver Line opened, 840 new rental apartments came on the market annually, more than double the 371 units that came on line in the previous four years.

Funding

The $2.9 billion Metrorail extension was paid for by increased tolls on the Dulles Access Road as well as state and federal funds. However, an additional estimated $2.8 billion in other transportation infrastructure was needed to support the increased density and transform Tysons into a walkable urban place. Where would this funding come from?

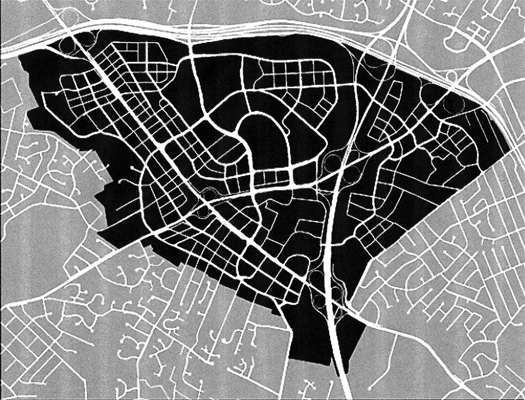

Tysons property owners now contribute to both a Tysons-wide Road Fund and a Tysons Grid of Streets Fund to increase walkability and put in new streets to break up the super-blocks that have long dominated the area. As the county’s 2017 Tysons Progress Report says, “All new or reconstructed road improvements will include pedestrian facilities and many will include bicycle facilities.” The county’s board of supervisors recently increased the 2018 contribution rate for these two funds to a combined total of $13.21 per floor-area ratio (FAR) square foot for commercial property.

A third transportation fund, The Tysons Road Fund, which has been in existence since before the 2010 comprehensive plan was approved, requires an assessment of $4.46 per FAR square foot. A developer’s minimum assessment, payable upon obtaining a building permit, is now $17.35 per FAR square foot.

This contribution, however, reflects the base transportation fees, and generally does not represent the full upfront cost of transportation improvements associated with a specific new or redeveloped project. Additional fees fund unique on-site road improvements, nearby road and intersection improvements, traffic demand management studies and programs, traffic signals, etc. Total transportation fees therefore typically range from $25 to $29 per FAR square foot. These fees alone mean that Tysons has some of the highest-priced suburban land values in the country.

To put these fees in context, annual asking rents for Class A office space in Tysons now average about $40 per square foot; the one-time transportation fees for the three funds and unique assessments therefore represent 62.5 to 72.5 percent of annual rents. Compare this to New York’s Park Avenue Manhattan submarket, where Class A asking rents are about $90 per square foot, according to Cushman & Wakefield, among the highest in the country. Transportation fees there are about $62 per FAR foot, according to the New York Times, 69 percent of annual rents. In other words, Tysons transportation charges are about the same, relative to rents, as those in one of the most expensive office submarkets in the country.

These substantial transportation fees reflect both the high cost of infrastructure improvements for walkable urban development as well as the market’s ability to pay for the improvements, given pent-up demand and higher rents.

The Tysons Partnership

The comprehensive plan foresaw much increased cooperation among landowners regarding transportation management, human-scale infrastructure improvements and even consolidation and/or coordinated development plans. To date, that cooperation has primarily been through the Tysons Partnership.

The Tysons Partnership was officially designated by Fairfax County as the transportation management association (TMA) for Tysons. It has been responsible for carpooling and circulator management as well as the introduction of the metro area’s Capital Bikeshare network to Tysons.

The partnership, which describes itself as “a dynamic collaborative of Tysons stakeholders working together to accelerate the transformation of Tysons into a great American city,” has been taking the lead in ensuring “that the overarching goals and objectives of the Comprehensive Plan for Tysons are achieved.” Its work has involved wayfinding, entrance signage and street banners; organizing pop-up parks, murals, festivals and other events like bike races and farmers markets; and installing public art. The partnership also represents property owners in their interactions with the county, the local jurisdiction implementing the comprehensive plan.

The existing street grid for Tysons (top) limits connectivity for automobiles and pedestrians throughout the area. A more urban grid (bottom) will enhance connectivity for all modes of transportation. Fairfax County Department of Planning and Zoning

The partnership is not, however, taking an in-depth role in placemaking and place management. These functions will be filled by private developers and property owners.

The major responsibilities for implementation of the comprehensive plan are now in the hands of the private sector, which is taking advantage of the Metrorail and other infrastructure improvements and the substantial increase in zoning density to transform Tysons into a denser, more urban place. Many developers and property owners are in the process of creating walkable urban places through new development, placemaking and place management. (See “The Boro” below for more on the new development now underway.)

The Coming “Breakup”

At 2,400 acres, Tysons is far too large to be just one walkable urban place. Recognizing this, the comprehensive plan divided Tysons into eight different zones, anticipating that each would evolve independently. However, it now appears that the bulk of new walkable urban development will cluster around Tysons’ four Metro stations, as specified by the new zoning.

Over the next generation, five walkable urban places of about 300 acres each are expected to emerge: one each around the McLean, Greensboro and Spring Hill stations, and two at the Tysons Corner station – one on either side, anchored by the area’s two regional malls, both of which are already surrounded by substantial office and residential development. Each of these five places will have its own character, economic role, tenant submarkets, etc.

This means that only about 1,500 of Tyson’s 2,400 acres will become walkable urban places. The rest of the area will stay pretty much as it is today for the foreseeable future.

Future Challenges And Lessons Learned

The entire country and much of the world is watching the transformation of drivable sub-urban Tysons into a collection of walkable urban places. This process already offers the following five lessons:

- Massive investment in transportation and parks must be made upfront, by both the public sector and private property owners. Given unlikely future federal infrastructure spending, this funding will probably have to come from state and local sources, and must include private co-investment.

- Walkable urban places, with their complex mix of residential, office and retail products, are much more difficult to develop than stand-alone drivable sub-urban projects. The initial phase of any walkable urban project must achieve enough critical mass to create a “there there.”

- Not all of the drivable sub-urban space in an edge city will be converted to walkable urban development. Some of the existing office, retail and residential products will remain, and will still be able to attract tenants unable to afford the higher-priced walkable urban product.

- Conventional underwriting probably does not apply to these projects, especially in their early phases. Upfront investment in infrastructure and parks, along with some unproven product offerings, especially at the required rent or sales price levels, will require a leap of faith at times. Property owners will eventually profit from the increase in land value in subsequent phases.

- Place making is essential for success. Whether through a business improvement district, government-funded urban districts or private place management, extraordinary cleaning and safety services, festival management and promotion, park development and management, economic development and more are required, and do not come cheap.

Since the first projects following the opening of Metrorail have only recently been completed and the first phase of The Boro, Tysons’ first major walkable urban place, has not yet delivered, the jury is still out on Tysons’ transition to walkable urbanism.

What is known is that, if the largest edge city in the country can pull this off, other edge cities will take notice and follow Tysons’ lead. In fact, Fairfax County is already applying some of the new policies and practices developed for Tysons to the Reston Transit Corridor, where the Silver Line is being extended to Dulles Airport.

Christopher B. Leinberger is a professor at George Washington University School of Business and a partner with Arcadia Land Co.

The BoroThe new walkable urban place that is furthest along in Tysons is The Boro, a multiphase mixed-use project being developed by The Meridian Group. Although the company was initially skeptical about investing in Tysons, following the adoption of the comprehensive plan and the commencement of Metrorail construction, Meridian felt Tysons was “ready to transition … away from the suburban office park model and create high energy pockets where people want to be,” according to Gary Block, partner and chief investment officer with Meridian.  The Boro will feature vibrant streetscapes and greenspaces; its first phase will contain 1.7 million square feet of apartments, condos, office and retail space, including a 15-screen cinema. Courtesy of The Meridian Group The Meridian Group wanted a Tysons location that would allow it to begin with a first phase large enough “to dramatically change the perception and feel of that area, which would drive land value of subsequent phases,” says Block. In August 2013, the company acquired the three-building headquarters of SAIC, a major government contractor, adjacent to the Greensboro Metrorail station. The property included 630,000 square feet of Class B office buildings, a parking deck and a call option for additional land with 3 million square feet of FAR. SAIC leased back 130,000 square feet in one of the three buildings. The first improvement Meridian made was to add a new “front door” to the SAIC property to face the new Metrorail station, in addition to the original car-oriented entrance. Meridian then acquired a 765,000-square-foot portfolio of four buildings adjacent to The Boro on the east and a 210,000- square-foot building directly across Greensboro Drive to the south. This will allow subsequent phases of development to take advantage of the critical mass that will be created in the first phase. The rezoning of Meridian’s holdings allows a total buildout of nearly 4 million square feet. The Boro’s first phase will contain 1.7 million square feet of apartments, condos, office and retail space, including a 15-screen ShowPlace Icon movie theater and the largest Whole Foods Market in the U.S. Two parks and new streets will break up the super blocks. The Boro aims to create the walkable urbanity promised by the comprehensive plan when its first phase delivers in 2019. Office rents at The Boro have already increased from the mid-$20s annually in 2013 to the mid-$40s in 2018, following renovation of the existing buildings from Class B back up to Class A. Office rents at the new phase I office tower are in the mid-$50 per square foot per year. Condos will be priced at $800 per square foot, on average, and some early reservations have achieved $1,000 per square foot. The rental apartment market is still new in this location, but Meridian is projecting annual rents of $36 to $42 per square foot. There is plenty of room for apartment rents to rise, since Tysons apartments currently rent at a discount to those in the R-B Corridor and downtown Washington. The key, according to Block, will be to “co-brand our properties and integrate one into the other, creating co-dependence and allowing one to benefit from investment in the other.” This “more is better” value creation phenomenon is common to most walkable urban places. As you build more retail space, housing, offices and entertainment, the area improves over time. More people on the sidewalks attract even more people. This is also referred to as the “upward spiral of value creation.” Meridian has planned substantial additional development to reap the benefits of the critical mass it expects to achieve in phase I. |