Research directors and Distinguished Fellows share perspectives on the trends shaping the short-term and long-term outlook for CRE in Canada and the U.S.

Based on the wide-ranging discussion at the most recent National Research Directors Meeting, uncertainty remains a key driver of action — or in many cases, inaction — within the commercial real estate (CRE) industry.

Held by the NAIOP Research Foundation in September at CRE.Converge in Toronto, the meeting brought together research directors from CRE services, data, investment and development firms from across Canada and the United States to discuss tariffs, artificial intelligence and other X factors influencing the industry. Also in attendance were three NAIOP Distinguished Fellows, university faculty engaged in research related to CRE.

Tariff Impacts on Canadian Economy and CRE

Luke Simurda, director of research overseeing Marcus & Millichap’s Canadian operations, began the meeting with a presentation on tariff implications on CRE in Canada. He said Canada’s economy had started gaining momentum throughout 2024. As a result, CRE investors were preparing to deploy capital at the end of 2024. “Dashboards were starting to turn green, largely due to strong population growth, a friendlier interest rate environment and relatively sound fundamentals across the property spectrum.”

The outlook turned for the worse once tariff uncertainty clouded the market. The data didn’t show the impact of tariffs in the first quarter of 2025, Simurda said, “but when second-quarter GDP [gross domestic product] growth came out, it was negative. Canadian GDP contracted by about 1.6% annualized, and that was on the heels of a pullback in exports and widespread uncertainty entering business investment.”

Forecasters generally believe economic growth in Canada will begin picking up the latter part of 2026, Simurda said, “hopefully on the heels of more trade clarity, a more-friendly monetary environment, increased government spending on defense, and the potential for widespread infrastructure investment.”

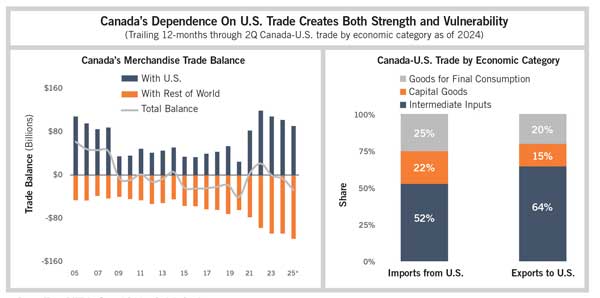

Simurda termed the short-term outlook as bleak, however. “Canada is so heavily dependent on trade with the United States. Canada holds a trade surplus with the U.S., whereas it holds a deficit with the rest of the world. … Tariffs are now taking a toll on trade with the U.S., and that surplus is narrowing.”

At the same time, data suggest the share of goods going to the United States that is compliant with the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement, and thus trading tariff-free, is as high as 90%. “Because of that, Canada holds a much lower effective tariff rate than the United States’ other largest trading partners,” Simurda said. “Over the long run … [that] could actually act as a tailwind for [Canada’s] economy, as well as for commercial real estate and property fundamentals.”

Investors Searching for Stability

In looking at the impact of tariffs on CRE in Canada, Simurda said the best place to start was the industrial sector. “First and foremost, industrial plays a fundamental role in cross-border trade flows, but also, industrial performance highly tracks the economy.”

Marcus & Millichap expects to see a continuation of muted net absorption of industrial space in Canada in the early parts of 2026 before potentially picking up later in the year. Simurda noted that inventory accumulations for wholesalers had spiked drastically in early 2025, largely due to tariff frontloading. “Usually in times of uncertainty, especially when supply chains are ruptured, firms tend to hold higher inventory levels,” he said. “They switch away from that just-in-time inventory to a little bit more just-in-case inventory. While I don’t think that’s going to really make a material difference [in industrial space demand], it’s something to keep in mind over the upcoming quarters.”

Where tariffs are taking the strongest hold is on the manufacturing side, including automobiles, metals and softwood lumber, Simurda said. “As you look at PMI [Purchasing Managers Index] surveys, inventory accumulation and future sales in the manufacturing side, it doesn’t look great in the short term. But there are some policies in place that could stimulate growth over the longer term. If Canada really does want to expand to more global markets in terms of trade, it will need to increase industrial capacity at home.”

Simurda said there is currently an oversupply of large-bay industrial in Canada, and thus higher vacancy rates. “The development economics on [small-bay] right now just don’t work, so people don’t build it. And because of that, vacancy is a lot more contained, sitting at around 2%. … The smaller-bay assets are a little bit more contained and shielded from tariff pressures simply because they service more local markets, whereas this larger-bay space is more prominent in global trade. That said, the under-construction pipeline [for large-bay] is beginning to taper, which is another reason we see fundamentals beginning to stabilize sometime [in 2026].”

Tariffs are also having an indirect effect on other Canadian CRE sectors, including multifamily and retail, Simurda said. At the beginning of 2025, there was a sharp decline in consumer confidence, largely due to tariff uncertainties. “We were expecting retail sales to follow suit … but [they] are actually holding up quite well,” he said. Second-quarter GDP data showed “consumption was up 4.5% annualized, and final domestic demand was up 3.5%. So consumption is that one bright spot right now in the Canadian economy.”

Sources: Marcus & Millichap Research Services, Statistics Canada

Moving forward, the expectation is that essential spending will begin outpacing total sales and discretionary spending as tariff uncertainty continues clouding the market, Simurda said. “That, in my opinion, is what is driving the narrative for grocery-anchored retail being the preferred investment in Canada right now. [Those assets] capture more spending in times of uncertainty [and] provide that stability we really need from an investment standpoint.”

“The most traded asset still remains industrial,” Simurda said in concluding his presentation. “However, that share is starting to decrease due to its exposure to tariffs. Multifamily has also been picking up the pace a little bit,” with investors currently favoring lower-rise, suburban multifamily. “But the preferred investment right now is grocery-anchored retail. … It offers strong in-place income growth, while at the same time, there’s upside to it from intensification or redevelopment over the longer ride.”

Capital Sitting on the Sidelines

Following Simurda’s presentation, Kim Somers, economic director, real assets and thematics at La Caisse, asked the assembled research directors for their thoughts on the current cost of real estate in Canada. “Technically, the market has repriced, but not that much in Canada,” she observed. “Do we still find real estate expensive or are the risk premiums that we’re seeing now the new normal? What do we make of this considering the high cost of debt too?”

Simurda said he didn’t think prices had corrected enough and that cap rates should have gone up more. “Canada’s market is supported not just by limited supply but by the dominance of institutional ownership. With deep-pocketed investors able to hold through downturns, forced selling is rare, and that stability slows price discovery,” he added.

Raymond Wong, vice president, data solutions, client delivery at Altus Group, said he thinks a substantial amount of capital is sitting on the sidelines because of the uncertain environment. He is hopeful transaction volumes will pick up in the spring. “If you talk to lenders, they really want to be active in the market, but they’re being very selective,” he said. “If you talk with the buyers, they’re all kicking the tires, looking at assets, where to go, but nobody wants to make a mistake at this point.”

Keith Reading, senior director of research at Morguard, said in looking at previous cycles, “everybody was waiting for the correction in value that never really came. And I think it’s the same this time around. People are waiting for a 150-, 200-basis point correction in cap rates.” He doesn’t see that happening, he said, because the Canadian market is comparatively small, its investors are generally conservative, and its “big players are not going to sell.”

A large portion of Canada’s real estate is institutionally held, so there is less liquidity than in the United States, added Anthio Yuen, senior director of investment strategy at GWL Realty Advisors.

Andrew Petrozzi, director, head of Canada research at Newmark, concurred: “You’ve got these large institutional holders, which are more prevalent in Canada, particularly in the Vancouver market, and they don’t want to destabilize the values of their own [office] portfolios, so they’re stuck. … They won’t transact because they can’t accept the lower values and what it will do to the value of the rest of their properties.”

Sentiments on Small-bay Industrial

Shawn Moura, vice president for the NAIOP Research Foundation, asked why small-bay industrial doesn’t attract more interest from institutional investors in the United States or Canada despite solid fundamentals.

Juan Arias, national director of U.S. industrial analytics at CoStar, said he has seen institutional players pursue small-bay Class A product, but there are fewer of these assets available relative to prepandemic levels and strong competition for those that are. “It’s hard to find a willing seller,” he said. He added that the “dry powder has shifted away from the equity play into the financing play” because the risk-adjusted returns are much higher on loans than on capital.

Canada doesn’t have much true small-bay product, Reading noted, “and a lot of what comes to the market has got some hair on it. You’ve got to have a plan for it if you’re hoping to bump the rents. For a lot of investors, that is too much of a headache. … It tends to be the private [players] that take it on because they’ve done them before.”

Arias added that many small-bay occupiers put a premium on remaining close to their local consumer bases. “They don’t need 32-foot clear, 40-foot clear [heights]. That’s not what they care about. … A lot of this smaller stuff over the past few years has been getting demolished. It’s disappearing because there’s higher, better use [and] multifamily’s taking over. The more that happens, the more important the locations are.”

Lisa DeNight, managing director, head of North American industrial research at Newmark, said a handful of U.S. markets have seen speculative small-bay development in recent years. However, in some cases, the new supply appears mismatched with local demand, “where it’s not necessarily near the infill tenant who would want to upgrade to a more modern facility,” she said.

According to Newmark data, the small-bay segment has experienced net outflows of occupancy for the past two years, DeNight added. The enduring benefit of small-bay is the diversification of its tenant base, which helps cushion against vacancies. The segment’s prospects are important to mention, DeNight said, “especially as we look to a slower growth, potentially higher inflation outlook for the United States.”

Arias said the push for higher rents is causing some churn among small-bay tenants in the near term. “But you’re still targeting 80% to 90% of the lease activity, [and] you’re more likely to find a tenant to backfill that space than in the big bulk distribution stuff. … I do think in the medium to long term, [small-bay] is still an even safer play than” large industrial.

The Outlook on Office Space

Phil Mobley, national director of office analytics at CoStar, said he was surprised there hasn’t been more activity around significantly discounted sublet space in the office market. “Your very top-tier occupiers have wanted this first-generation direct space with long terms and huge concessions,” he said, “and now that that stuff is drying up … they’re just doing without.”

“Their mindset now is ‘what do I need today?’” he continued. “They’re not taking on that extra 10% for growth because a) they’re not hiring; b) they’re short term, they’re cost-conscious; and c) if they do start hiring again, they can use the same tech that let us work remote for two years to flex and maybe find some other space. But the phenomenon of just doing without rather than settling for something that’s less than perfect is really an important one right now.”

Omar Eltorai, senior director of research at Altus Group, said being in an ongoing period of uncertainty has caused companies to delay making additional investments in their businesses. “And on top of that, you have a huge structural change to our economy, which is AI … and we’re not even through the first inning of that.”

“We’re entering an exciting phase of discovery as companies explore how to grow and how to harness AI’s incredible potential to elevate workflows and empower an evolving workforce,” said Cornelia Le, director, Canada strategy and research, private markets, real estate at Manulife Investment Management. “This transformation is unlocking new levels of innovation and creativity and smarter ways of working. For office spaces, this shift represents a tremendous opportunity to reimagine workplaces — spaces that inspire collaboration, integrate modern tools and enable the future of business. The story for office is ultimately one of transformation — moving away from obsolete spaces that no longer serve the evolving needs of people and businesses and creating environments that are agile and future-ready.”

More companies will look at converting their older office buildings to residential or other uses, Reading said, especially if they are near mass transit. “But each individual building will depend on where it is located, the value of that building and the value of that site. Some sites are better than others.”

Trends Worth Monitoring

Participants concluded by touching on several trends that could have ramifications for various asset types over the long term.

Wong mentioned higher unemployment for younger workers, especially among those 18 to 25, and said this could impact both office space and housing. “AI would definitely make a big difference in overall efficiencies regarding how we use the space and how many employees we actually need on-site versus off-site,” he said. On the proptech side, “we haven’t really seen … the real influence on construction yet.”

Mark Stapp, Fred E. Taylor Professor of Real Estate and executive director of real estate programs at Arizona State University, said he is monitoring the United States’ aging population. The Census Bureau has projected that by 2030, 1 in 5 Americans will be of retirement age. “That’s going to create a labor problem for us, and it’s going to shift how we work and who those employees are,” said Stapp, a NAIOP Distinguished Fellow. “You couple that with immigration policy, and it’s going to cause … a substantial impact on employment sectors.”

Mobley suggested the wealth transfer from the baby boomers to the millennial generation could be more disruptive and unpredictable than most are expecting. He doesn’t have full confidence in the narrative that the silver tsunami will automatically translate to built-in demand for more medical office and senior housing, he said. One alternative could be a rise in multigenerational households deciding it is more efficient and less costly to care for senior family members at home.

Eric Gaus, chief economist at Dodge Construction Network, said he believes an “uncertainty premium” could be present for the next decade due to the political environment in the U.S. “We’ve been so predictable for so long, and now all of a sudden we’re not, and it’s going to be really hard to unwind that,” he said. “I think that speaks a lot to why investors aren’t doing anything right now.”

Also significant, Eltorai said, is that both major political parties in the U.S. are acknowledging the reality of the housing problem. “I think they’ll approach it in different ways, but you’re seeing a number of cities starting to test the waters with different housing policies” involving incentives, zoning and financing.

Stapp wondered about the potential for reverse migration to cheaper markets as constraints to growth and climate-related risks push living costs up in markets across the Southeast and Southwest.

Arias said he believes employer costs are the stronger determining factor. “Florida has been outpacing all the other states in [business] relocations for the last decade, and that’s been driving a lot of our population growth,” he said. “I don’t foresee people going back to the Midwest or all these other regions because they have been falling behind in building these hubs of employment.”

DeNight said this scenario could be particularly interesting to watch over the next decade. Newmark has profiled billions of dollars in manufacturing investment taking place in secondary and tertiary “value” markets.

Jonathan Rollins is the managing editor of publications for NAIOP.